“Propaganda of the deed”/ Historical anarchism, my grandfather as an example

Photo: Private collection

What is anarchism? The term has consistently been used as a pejorative— depicting anarchists as insurrectionists, a black bloc, bomb plotters and terrorists. But anarchism is primarily a political stance that has resurfaced repeatedly for centuries, regaining currency and finding new supporters. Anarchists rebel against the state, dogmas and functionaries. That is why we called ourselves “non-dogmatic groups” or “spontis” (from spontaneous) in the 1970s. It was the sponti women who (re-)founded the feminist movement. For that reason it is worth taking a closer look at anarchist theory and tradition.

In the 1970s, the ‘68er movement split into many factions of a Leninist, revisionist or Maoist bent, each following their various dogmas. The membership numbers of the non-dogmatic left, in contrast, remained tiny, less than 1 percent of the overall Left.

We had no dogmas, no pioneering thinkers and no leaders. How were we supposed to find out what would make political sense now? Which objectives were worth pursuing? How should we proceed? Among the dogmatists, all these questions were handled by a small leadership circle or even dictated by the GDR or China. We non-dogmatics sought inspiration elsewhere.

For instance, we read the works of Frantz Fanon,[i] the publications of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense[ii] and the memoirs of the Russian-American anarchist Emma Goldman,[iii] and maintained contacts with French and Italian autonomous groups. The writings of Mikhail Bakunin were resurrected and distributed as pirate editions, and naturally those of the Tupamaros,[iv] the South American urban guerilla group.

The non-dogmatic groups were interested in finding a path to revolution without having to submit to the dictates of a party. The Cuban revolution showed that this was possible. Its militant leader, Che Guevara, abandoned his ministerial posts in 1964 at a time when the party in Cuba, and with it ties to Moscow, were becoming increasingly strong. True to his principles, he went to Africa as a guerilla and later to Bolivia. His portrait hung in many communal apartments not just because he was handsome, but also because he rejected the party establishment.

The mistrust of left-wing claims to power also has a long tradition. Anarchism means the absence of authority or rulers and is an anti-authoritarian tendency that became influential in many countries in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The anarchist movement extended from Russia to America; its champions fought and died for freedom, from the Paris Commune in 1871 to the Spanish Civil War in 1936.

The nineteenth-century theorists of anarchism included Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Mikhail Bakunin, who by the way spent many years in Switzerland. Their goal was not to capture but to destroy power. With their basis in small trade unions, the anarcho-syndicalists, for instance, sought to use strikes to topple the existing order and build a classless society with no authorities. The Russian anarchist Sergey Nechayev, in contrast, called for “direct action,” the “propaganda of the deed”: terrorist attacks on representatives and institutions of the ruling system were supposed to motivate the oppressed to act on their own behalf. The idea that “terror from below” is a natural right in response to “rape from above” was taken up a century later in the writings of Ulrike Meinhof and used to legitimate terrorist attacks by the Baader-Meinhof group, the Red Army Faction (RAF) and the June 2nd Movement. The RAF, however, was anything but anarchist; it was tightly organized and used Leninist vocabulary that anarchists utterly rejected.

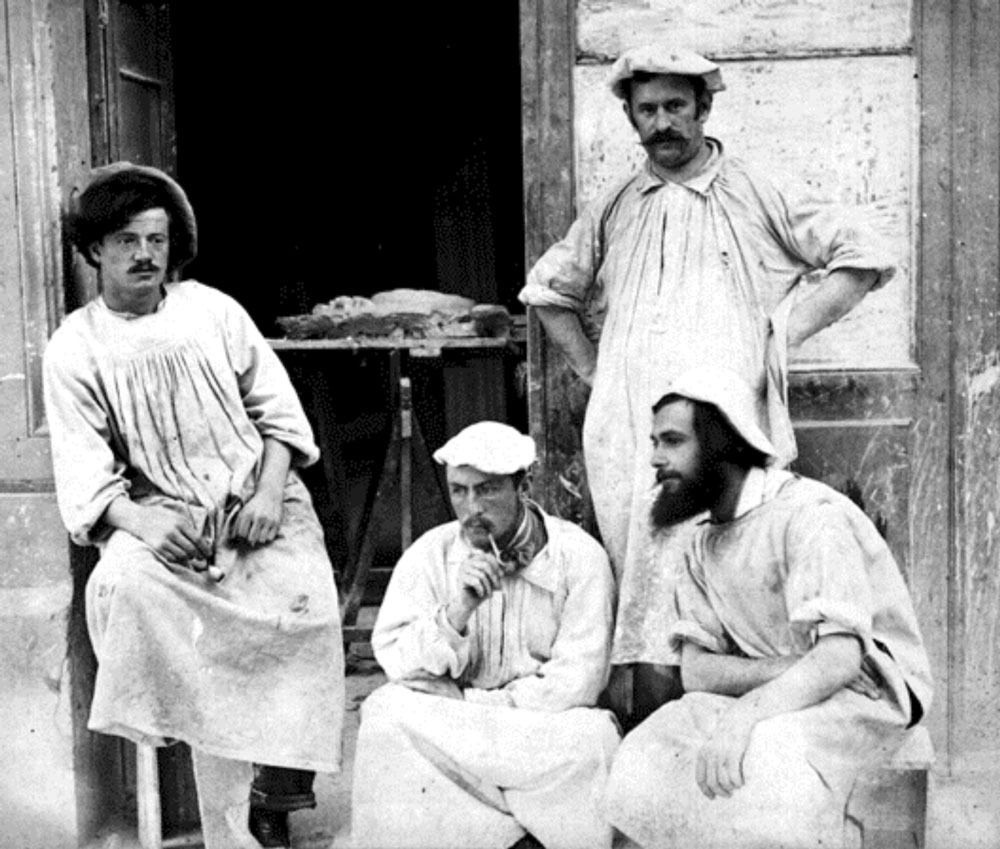

Photo: Private collection

Etienne Perincioli – An anarchist 1906

My grandfather, Etienne Perincioli, was an anarchist activist around 1900. His example vividly illustrates the timelessness of anarchist themes.

As a sculptor from the northern Italian region of Piedmont, my grandfather worked in those days in the large Swiss workshops that supplied the sumptuous new hotels along the shore of Lake Geneva with sculptures and stucco ornaments.

He and his colleagues resisted attempts by the large building workers’ union to organize them. They had no desire to finance apparatchiks who also wanted to tell them what to do. For that reason they organized independently and went on strike when it seemed most opportune—i.e., when they had plenty of commissions. That was how my grandmother explained it. He and his colleagues built explosive bombs (but only for fun, my father said). Grandfather even founded a commune, but the division of labor at home didn’t work out. Disappointed, he noted that there were profiteers even among colleagues. In 1905 he married my grandmother, a girl from Interlaken who also worked on Lake Geneva. She later told me with a shudder how scared she had been during the time when she and Etienne took in a family sought by the police.

In 1908 he settled with his wife and child in Berne, but when he applied for citizenship the police records of his anarchist activities got in the way. Now a very busy artist in the city, he had friends in the local establishment, which he would belong to soon as well. He bequeathed a large caliber pistol from this time to my father, which I in turn appropriated when the anarchist movement was revived fifty years later, and I also considered myself part of it.

[i] Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Constance Farrington (New York, 1961).

[ii] Cf. the chapter Searching for a Theory.

[iii] Emma Goldman, Living My Life, 2 vols (New York, 1931, 1934).

[iv] In the 1960s and 1970s they engaged in armed actions, kidnapped prominent individuals and robbed banks. They were the models for the West Berlin Tupamaros, the forerunners of the June 2nd Movement.