Vier Frauen auf dem Kriegspfad/Die Suche nach neuen Verhaltensweisen und Frauenbildern/Entstehung der Bewegung des 2. Juni

Ich verbrachte den Sommer und Herbst 1970 mit den Frauen von Agit 883 , aber wir kamen dort mit dem „Frauengeschäft“ nicht wirklich voran. Die Männer instrumentalisierten und schüchterten uns ein. Dann wurden Annerose Reiche und ihr Freund wegen Brandstiftung verhaftet [i] und der Rest der Blues [ii] ging in den Untergrund, wodurch ihre Wohnung am Cosimaplatz [iii] frei wurde. Dies gab uns die Möglichkeit, dort eine unabhängige Frauenkommune zu gründen.

Die betreffende Wohnung befand sich im zweiten Stock, aber auch anderswo im Gebäude geschahen historische Ereignisse: Im Erdgeschoss wohnte der Autor Peter Schneider, in dessen Küche Helke Sander und Marianne Herzog ihre Idee entwickelten den selbstverwalteten Kinderladen im Dezember 1967. [iv] Im dritten Stock wohnte Sigrid Fronius, die wir Cosima nannten, als sie drei Jahre später im Berliner Frauenzentrum und der feministischen Zeitschrift Courage aktiv wurde.

Auf unsere Frauenkommune im zweiten Stock folgte 1971 eine Gruppe, die Arbeiterinnen des Telekommunikationsunternehmens DeTeWe organisierte, wo ich auch Erfahrungen sammelte. So fanden wir uns auch für Treffen der Betriebsgruppe am Cosimaplatz 2 ein.

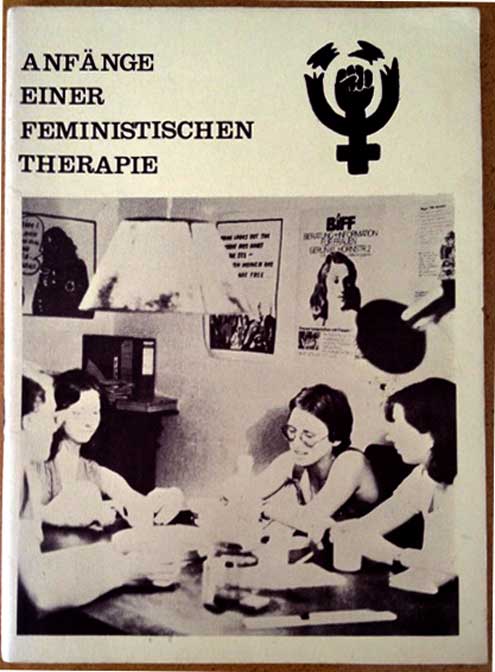

About two years later feminists took over this same apartment. They included two of the Flying Lesbians, Monika Savier and Monika Mengel, and the rock band wrote some of the movement’s most important songs there.[v] Monika Schmid, Biggi Wilpert and Lilia Bevilaqua also moved into the commune. They had started “Counseling and Information for Women” (BIFF) at the Women’s Center and were now working on translating and publishing the brochure “Beginnings of a Feminist Therapy” under the motto “Therapy is change—not conformity.” The fifth Monika at Cosimaplatz, Monne Kühn, set up the counseling center for homosexual women at the Lesbian Action Center (LAZ) around the same time.

Sitting at the table in the commune on Cosimaplatz. From l to r: unidentified, Monika Schmid, Biggi Wilpert and Christa Müller, 1974 Photo: Monne Kühn

But to get back to the winter of 1970/71, in what follows I describe how we women endeavored to develop actions to mobilize women. I would like to illustrate how difficult we found it to carve out a path for a women’s movement without any historical role models.

The Commune Women

Angela Luther, a teacher formerly married to the Hamburg filmmaker Hark Bohm, came from the Hamburg upper class but was working as a packer in a factory. She had a controlled and dashing manner, was very tall, with long legs in jeans and boots, short, straight brown hair, fair-skinned and freckled. She had previously been active in the Spandau Basisgruppe (grassroots group) within which she had helped to found a women’s group. The schoolgirl Verena Becker was active there as well. The 17-year-old moved to the commune at the end of 1970 after graduating from high school.

Angela Luther and Verena Becker had already read Valerie Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto in the women’s group of the Spandau Basisgruppe. They had “organized” the books as a group, that is, they went to the bookshop and said, “Give us 20 copies.” One of the women took the books and disappeared while the rest of them shielded her.

Paragraph 218 was an obvious target for actions. A doctor who had raped women had a warning spray-painted on the door of his practice and butyric acid poured through his mail slot.

There were several sub-groups within the Spandau Basisgruppe, but the women’s group had no vote, although the apprentice group did. That led to Angela Luther and Verena Becker leaving the Basisgruppe.

Verena always wore a black scarf tied around her neck. She had a part-time job with telephone directory assistance, cut classes at her vocational school and was very uncommunicative, but always like a tightly coiled spring. When I moved out of the commune she shot at me with a gas pistol, her way in those days of expressing her displeasure at losing someone.

Helga (last name unknown) was a religion teacher and the fourth member of the group. I don’t know whether she had a job; at any rate her work didn’t seem to interfere with the rest of her life. Her boyfriend was a fellow student at the film academy, the most eccentric scatterbrain in my class. On the one hand, he had a charming lack of seriousness, but on the other he was a dedicated moocher who ate, bathed and slept at our place and even borrowed our clothes without ever asking or offering anything of his own in return except a constant stream of chatter, which rendered all other conversation impossible. We tolerated him for months for Helga’s sake.

Helga, slim with blonde curls, a real Berlin native, managed with phenomenal intuition to talk her way out of sticky situations: We four often went out together at night— postering, stealing gasoline, spray-painting slogans. One night, after we had sprayed half of Moabit, we were stopped by the police. Helga immediately had the right story: We were four tipsy girls on their way home from a party. While the officers inspected the car she embroiled them in such funny banter that they clearly didn’t dare notice the evidence—we had paint on our hands and the car was full of empty spray cans. At home we found Helga’s boyfriend shivering at the window wrapped in a bathrobe (one of ours), awaiting our return. He had been so afraid for us.

What were the objectives of the women’s commune and how did we try to achieve them?

“Refusal to conform”

For me, this refusal consisted primarily of shedding my well-bred upbringing. So I learned to steal—food, gas, cigarettes— which I found quite difficult. We didn’t have a key to our apartment, but only a picklock made out of a wire coat hanger. This had the advantage that we could also enter many other apartments without having to ring the bell, including the other communal apartments in the building, which were lucky enough to have pay phones. You could also use the picklock to fish cigarettes out of vending machines.

We also tried reversing traditional roles, driving around at night alongside men and chatting them up through the window until they were very nervous, then calling, “Don’t worry, Sweetie, there’s nothing to be afraid of!”

After we had done this with guys a few times we tried it with a woman. We were curious to see how she would react. But the very first one was happy to let us buy her a beer. In the pub we asked her “Man, why did you come with us anyway?” She found us so nice and this had never happened to her before; she was just an ordinary office worker.

A “new identity as women”

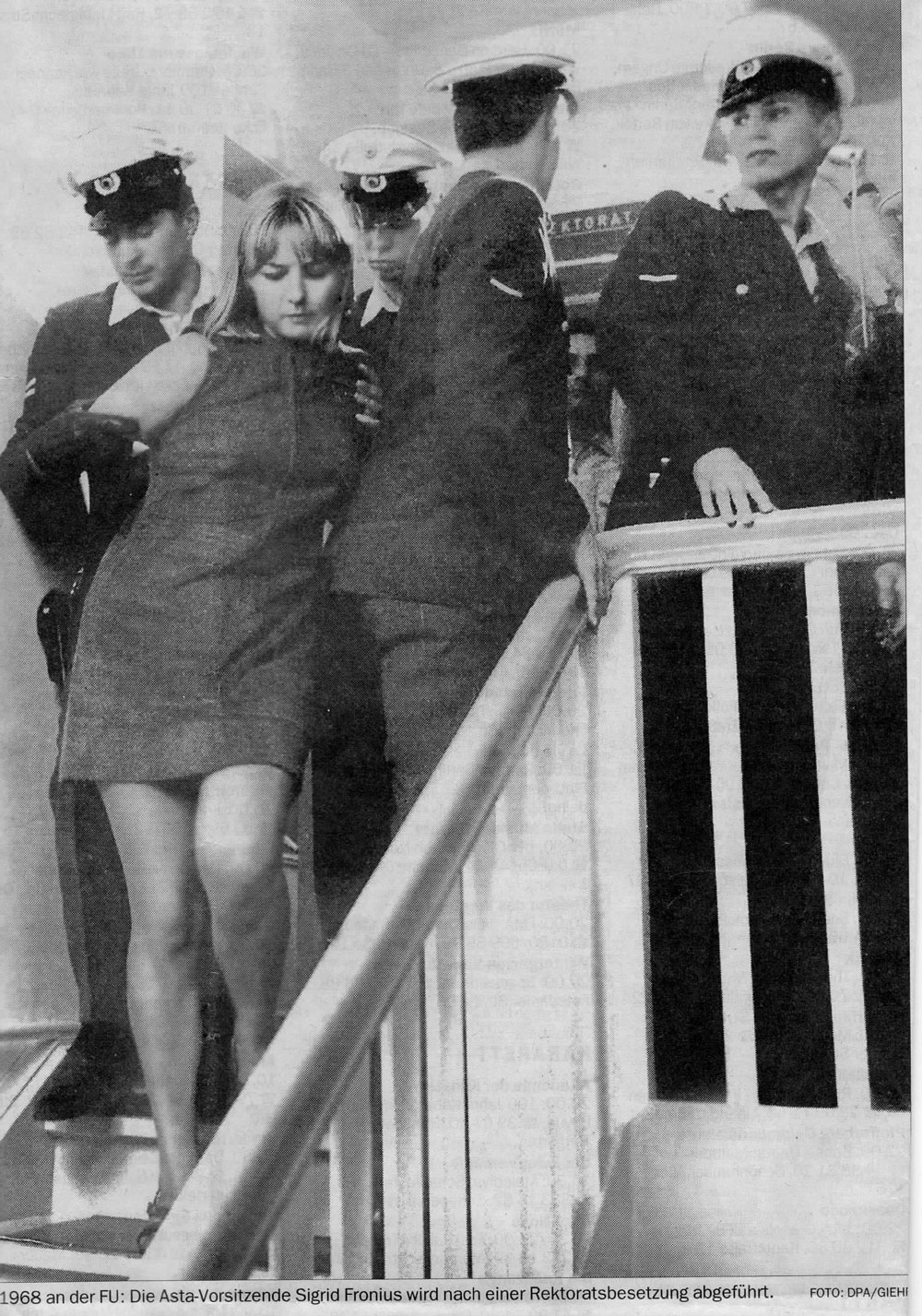

I think we appeared quite martial, at any rate, when the more respectable student group around Sigrid Fronius in the communal apartment over us planned an action they asked us to participate as reinforcement. Sigrid was known as a student leader. I found it inappropriate for a woman who had a certain amount of clout—she was the first woman to head the FU student council—to sleep under a poster of Che Guevara, and I defaced it with obscene drawings. As unbearable as I must have been in those days, I remained friends with Sigrid for many years, and we met again at the Women’s Center.

Part of women’s new image was standing up to male aggression. We were doubtless inspired by the recent pictures of black people defending themselves in the form of the Black Panthers. The first test came after my first and only karate lesson. We had decided to have a beer in the little bar on Sentastrasse. The woman who owned it welcomed us as her saviors: Here were four self-assured women with a completely different way of life. She sat down with us and complained about being abused and ripped off by her partner. She was at the end of her rope. Then this man built like a barn door entered the bar, helped himself to money from the cash register and looked over at the owner whispering with four strange women. He began cursing us and telling us to leave, but the owner just kept the rounds coming and asked us to stay.

The situation now became hopeless and threatening. Helga went to a men’s communal apartment on Cosimaplatz for reinforcements, but returned with only a junkie. The bruiser locked the door, saying “Nobody comes in or out, we’re closed!” Angela jumped him to get the door open, but was grabbed by two Turks. Verena went down; I kicked the bruiser in the balls but apparently missed because he attacked me all the more furiously and gave me quite a shiner. Then he lifted a bar stool to hit Verena, who was passed out on the floor. I managed to get the stool away from him and drag Verena out of the bar. That was how we got our first black eyes. The man Helga had brought along was no help either: He threw a cobblestone through the window from outside, but it hit the female bar owner in the head.

Solidarity with and devotion to our sisters

As in other communes, we laid the mattresses together in one room to form a huge bed where we all slept. The commune resembled a giant nest; even the strong and familiar smell upon entering was homey. We cooked and ate and spent entire days and nights together. There was a great tenderness: I could wrestle with Verena or make out with Angela every time we ran into each other in the apartment—until the night I confessed I was a lesbian. I can still remember how she went rigid in the dark and finally said, “I can’t kiss you anymore from now on.” She did in fact need men for sex. She picked them up here and there, but she was always back home in the morning. We felt a bit abashed, as if she was disloyal to us somehow by going with these guys when we did everything else without them.

Around this time I saw a film that represented a kind of political program for me: In The Magnificent Seven[vi] a few down-on-their-luck gunfighters join forces to help a Mexican village defend itself against bandits—a hopeless case they approach as a sporting challenge. They do it free of charge for a change, and also not out of political arrogance or a helper syndrome. First they must inculcate the intimidated ranchers with self-confidence and a will to resist, then build up their fighting skills and compensate for their military inferiority with clever tactics to win the battle.

The militant actions of our women’s commune were intended to underline women’s issues and show that there were women prepared to throw Molotov cocktails and use guns on behalf of women. Our actions were well received, even among apolitical women. People accepted militant actions in those days—before the time of the Red Army Faction—if we conveyed the reason for them. We now know where this militancy, which was divorced from real concerns and increasingly engineered, leads.

Nowadays I am ashamed of how abstractly and theoretically we chose our objectives in the winter of 1970/71. If a suggestion for an action generally fit the concept, we put it into practice. The main thing was that something happened. Once, four of us tried to disrupt a beauty contest. We failed abysmally, since we were verbally vastly inferior to the host and the enthusiastic male and female audience and people simply laughed at us. The fact that we spent a good deal of time on milk prices shows how clueless we were. The price of milk had just been raised and we thought that we could get women to protest this. We looked desperately for occasions for actions. And since we were not integrated into a grassroots group and the women of the former Action Council had retreated for training, we were left hanging with our burning desire to do something. For that reason, we finally planned a sort of women’s neighborhood center in the form of a laundromat and rented a shop on Liebenwalder Strasse.

The women join the June 2nd movement

I moved at this point, however, because I had found a girlfriend—Anke-Rixa Hansen— and went to live with her in Kreuzberg, and thus was no longer part of the commune. I worked for a few months doing installation for the phone company (DeTeWe). One day I saw Angela Luther’s picture in the paper. She was suspected of participating in a bank robbery and was being held in jail, but was released when witnesses were unable to identify her in a lineup. She went underground, joined the RAF and disappeared forever in 1972.

Verena was the only one left in the Liebenwalder Strasse apartment: The rent had to be paid, so the Schwarze Hilfe (Black Aid) moved in, a group that helped political prisoners, but also many destitute prisoners—mainly young men. Later, members of Schwarze Hilfe considered themselves part of the June 2nd movement, but they did their own things as well.

At that time the guys from the Blues gathered under the name June 2nd Movement.[vii] The members included Georg von Rauch,[viii] Tommy Weisbecker,[ix] Michael “Bommi” Baumann, Ralf Reinders, Peter Knoll, Fritz Teufel and Philip (Werner) Sauber,[x] Annerose Reiche and Ina Siepmann. I had met Inge Viett at Anke-Rixa Hansen’s place and brought her to the women’s commune at Cosimaplatz. In the summer of 1971 she joined forces with Verena Becker at Liebenwalder Strasse and soon became a leading woman in the group.

In Summer 1971 I visited Angela Luther and Verena Becker one last time at Liebenwalder Strasse. We stood on the street and tried out my motorcycle, and I told them about my diploma film, which I was preparing with the women’s group in the Märkisches Viertel.[xi] This enraged Angela, who attacked me as a traitor and ripped my film project to shreds. She expressed a hatred I had never experienced from her before. Back in my own kitchen in Kreuzberg, I felt like shoving a knife in my belly. I didn’t do it, but the image stayed in my mind as a reflection of how much I wanted to destroy myself.

There were several other people who tried, for various reasons, to prevent this film from being made. They felt provoked by my project, as Angela had. Perhaps at that moment she realized that I had made friends with self-confident women, women of the “working class,” and was collaborating with them on a project with a future, while she was on a different track, one ultimately leading to death and destuction.

The second aspect that made her furious was that I was about to finish my degree. Despite all my anarchist activities, I had never lost sight of that objective. I saw a future for myself in this profession, a chance to accomplish something, and I identified with my work. That was not the case for the others, except for the construction worker Bommi Baumann. Most members of the June 2nd Movement had dropped out of training programs or studies. The few who had trained for a profession rejected it: teaching in Angela Luther’s case and childcare in Inge Viett’s. Perhaps that is also why only Bommi Baumann managed to escape—he could return to construction. As a foreman he had to be assertive and loud and bang on the table. “It was only when the job was over that I realized that it had gradually made me normal again.”[xii]

In the guerilla

The June 2nd group had a theoretical base similar to the “Gauche Proletarienne” in France or “Lotta Continua” in Italy—that is, to give a militant solution to labor conflicts in the factories. When the people in factories are falling over from the bad air, then the owner’s villa must be set on fire, to show the people you can defend yourself if you attack the guy directly…. We took part in the mass actions against the B.V.G. [Berlin Public Transit system] price rise. B.V.G. ticket machines were destroyed. This was the sort of basic guerilla work which we influenced. … To develop militance in the community groups, and in the factories, to develop factory guerillas from that source …. Leaflets, demos, stickers, neighborhood aid, a sort of red assistance in the communities on the one hand, and also getting involved with the problem of group homes for youth. …

And on the other hand, supporting a clandestine cell, which is not recognized, whose cadres do the cloak-and-dagger operations and support mass actions through them.… It wasn’t a matter of abstractly building a Red Army. If it isn’t rooted from the beginning, I just don’t know what it’s supposed to do….

However,

A guerilla apparatus that is already at a higher stage of development makes so many demands on you that you don’t have time for other things. The logistics work makes incredibly high demands. … Later we started cracking open cigarette machines, out of need or other similar nonsense because we just had nothing left to eat. …Then we got to the point of doing bank robberies and simply getting our money that way. That is already a different form of action, because for the first time you appear with a gun.[xiii]

After Bloody Sunday in Derry, Northern Island in 1972, the June 2nd Movement wanted to send a signal and placed a bomb in the British Yacht Club in West Berlin. Bommi had helped to build it, but it did not explode at night as planned but only the next day when the boat builder Beelitz found and handled it. The women of the June 2nd Movement pushed aside my accusations regarding his death, saying that he had been working for the British after all. They gave not the slightest indication of misgivings or regret. From then on I regarded them not as rebels but as criminals.

Bommi left the group after this act and spent several years on the run. He later called for an abandonment of the armed struggle, but could not get through to them.

While the people of the June 2nd Movement saw that their actions were not leading to the discussion or change they had hoped for, they never reflected on or questioned their own path. Not long thereafter most of them were in prison. Now the aim was to survive their years of incarceration!

To be sure, they managed to obtain Verena Becker’s release by kidnapping Peter Lorenz,[xiv] and Inge Viett escaped from the women’s prison twice, but they carried on as “senselessly” in the underground and remained as driven as before: “Shit, it’s not all as easy or clear or coherent as it used to be….” I simply lacked the space to consider my actions and make decisions,” one of the women involved noted in retrospect.

[i] See the chapter Militant Women.

[ii] On the Blues, see also the chapter Militant Women.

[iii] Cosimaplatz 2, in the Friedenau district of Berlin.

[iv] See the chapter Bread and Roses.

[v] See the chapter Festivals/Flying Lesbians.

[vi] The Magnificent Seven (1960) was directed by John Sturges and starred Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson and the young Horst Buchholz.

[vii] The June 2nd Movement was named after the date in 1967 when the student Benno Ohnesorg was shot dead by police during a demonstration against the Shah of Iran.

[viii] Georg von Rauch was shot dead on Dec. 12, 1971 in Berlin.

[ix] Tommy Weissbecker was shot dead on March 2, 1971 in Augsburg.

[x] Philip (Werner) Sauber was shot dead on May 9, 1975.

[xi] See the chapter Women Make Movies.

[xii] “40 Jahre nach 68,” interview in SEIN, July 1998.

[xiii] Bommi Baumann, Wie alles anfing (Munich, 1975), pp. 100–101. English: How It All Began: The Personal Account of a West German Urban Guerilla, trans. Wayne Parker and Helene Ellenbogen (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 1971, revised edn 1981, reprint 2001), p. 87–89. Translator’s note: I have slightly revised the translation to correct minor errors.

[xiv] Die Bewegung des 2. Juni entführte Peter Lorenz drei Tage nach der Berliner Bürgermeisterwahl 1975 und erzwang damit die Freilassung von sieben politischen Gefangenen.

Sigrid Fronius, die erste AStA-Präsidentin einer deutschen Universität, wird bei der Besetzung des Büros des Präsidenten der Freien Universität (FU) Berlin 1968 von der Polizei abgeführt hatte das Fenster eingeschlagen und so die Besetzung ermöglicht.