At the end of 1968, the political movement split into a number of factions. The revolt at the Film Academy ended dramatically: The most active and creative students had been removed as part of disproportionate punitive action. But what was to become of the other students, who also saw themselves as radicals but for some reason had not participated in the occupation and were therefore spared expulsion?

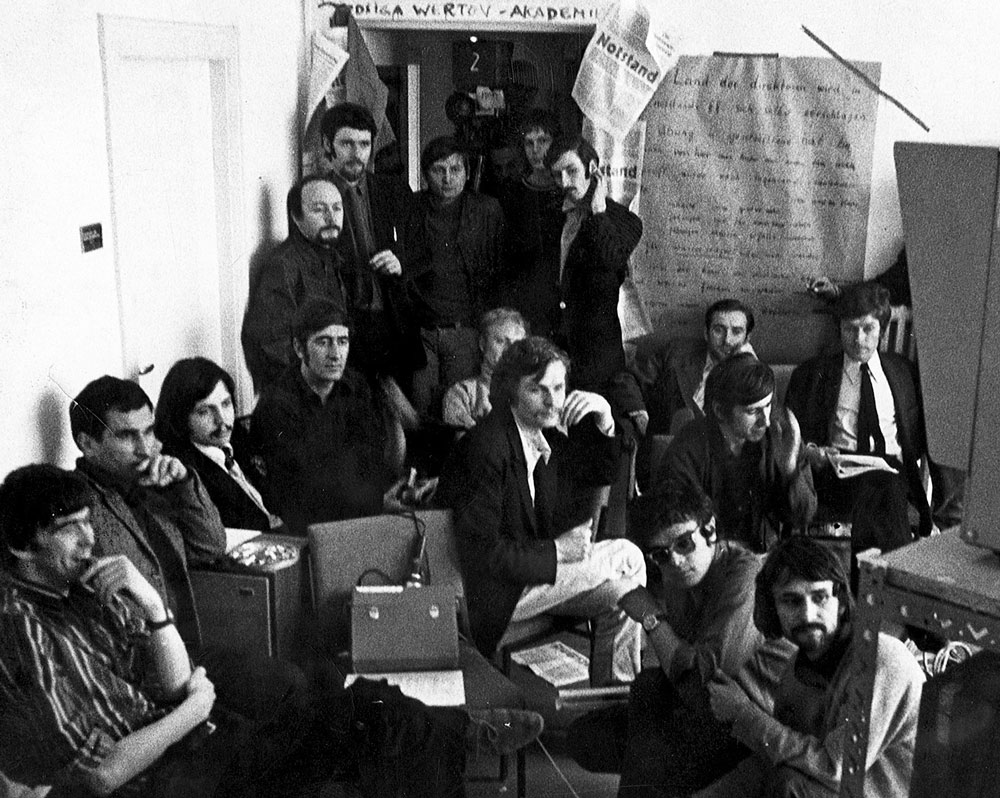

First and second year students of the Filmacademy in 1967—the picture still includes those who were later expelled: (fr. l to r) back row in the doorway: Jean-Francois Le Moign, Max Willutzki, Hans Beringer.

Along the wallfrom l: Eik Gallwitz, Reza Dabui, Michael Geissler, Daniel Schmid.

Half covered: Enzio Edschmidt, Christian Ziewer. Row in front: Gerd Conradt, Frank Grützbach. Crouching: Harun Farocki, Holger Meins. Photo: Uzo Kempe

Guilt pangs and a need for subordination

Today I suspect that the exaggerated expectations that the remaining left-wing students subsequently placed on themselves and their films were rooted in the kind of guilt pangs often observed among survivors, as if they had to prove now more than ever that they were fighters.

The academy was now run by the “academic council” demanded by students, instead of by the previous “enemy”, the directors. The only ones left to castigate were fellow students and their films. They themselves were so stymied by their own ambitions that they scarcely produced any films.

Helene Schwarz, a central institution at the Film Academy, recalls:

Then these party-line discussions started, which they used to bring each other down. Every time a student film came up for review, people asked: ‘Does it serve the people?’ ‘No, it doesn’t!’ and so every film made by a member of the other political group was savagely picked apart, which destroyed a lot of things. This kept many students from developing because they were afraid of these review discussions.

Nowadays they are constantly asking each other’s opinions and helping one another. Back then they wouldn’t let anybody into the cutting room, they were scared of each other.

A very unfortunate situation that persisted for years.

Many people simply stayed away after that.

The objectives had changed. Where previously the students had fought for their own interests, achieving a reform of the conditions of study and addressing the question of their own rights, thereby modernizing the institution itself, now they rejected the representation of their own interests as impermissible, calling it “petty bourgeois and apolitical.” The motto now was “to serve the people.” But since they had no relationship to “the people,” they could propose completely abstruse theories about what was useful to the “people” and how they should be educated, theories that sometimes harked back to Marx and Lenin, and sometimes to Trotsky, Mao or Bakunin. And so the Film Academy, like all other institutions of higher learning, got its factions of Marxist-Leninists, Communist League and Communist Student Union, which now vied with one another for influence. Instructors were chosen by party affiliation, and those applying to study at the Academy who did not belong to a particular faction or have friends there had very little chance of getting past the relevant committees, which now also had students as members.

Documentary film group

Only our “Wochenschau group” – a student film group under the wings of documentary filmmaker Klaus Wildenhahn – was spared this savaging process. Unlike the majority of film students, who already had university degrees, Klaus had chosen as his students a cook, an actress, a photographer and me as the baby of the group. As long as Thomas Mitscherlich, a university graduate and our oldest member, did not harangue us with his abstract outpourings, we had a creative safe haven here, surrounded by a sea of embittered debates, in which we could air our observations and fantasies uncensored.

For instance, we spent weeks discussing a film project that was intended to show what would happen if all of the young people left Berlin. In those days the student movement met with bitter hatred among native Berliners, whose anti-Communism—the Wall had been erected just eight years before—was only too understandable. Their constant refrain was “So just move over there” [i.e., East Germany, if you dont like it here].

In the early summer of 1969, news of the occupation of the Catholic students’ dormitory on Suarezstrasse in Berlin’s Charlottenburg district broke in the midst of these pipe dreams, and it was immediately obvious to Gisela Tuchtenhagen and me that we had to go where the real action was. The next day we moved into the squatted building and began filming as participant observers. The other part of our Wochenschau group accompanied a bus driver and conductor (they still had them in those days) from the BVG municipal transportation company at work over the next few weeks. Thomas Mitscherlich had concluded that this segment of the working class would be decisive for a potential revolution. He rejected student actionism (e.g., occupying buildings) and stuck to theoretical constructions. Later he tried to force us to read the Marxist theorist Ernest Mandel, but when he found himself unable to explain the term “surplus value” to us we refused to give reading Mandel a chance. And so the Wochenschau group clung to its cheerful cluelessness.

In the squatted building

Gisela Tuchtenhagen and I lived in the squat on Suarezstrasse until the autumn of 1969 and caught the bug of anarchist “adventurism.” At first we were still worried that the group of rockers who frequented the house might steal our film equipment, so we always slept with our camera and sound equipment within reach. In fact, one night the door did fly open and the rockers stormed in—bringing us a crate of freshly captured peaches!

The most poetic scenes in the film about the occupation of the student dormitory show these boys talking about their lives and their “positioning,” which was mainly a result of the street battles they fought side-by-side with the students.

One alien world after another opened up before me: First I became more closely acquainted with “bad boys,” then came the young boys who had run away from reform school. From them we learned about conditions in the children’s homes and went to talk to the warden responsible. We made friends with “cons” who told us about jail and their prison careers.

Apart from these “marginalized groups” and members of the lumpenproletariat, however, the building also still housed Catholic students whose sheltered world had been shaken up along with mine. I was very anxious to cast off my nice bourgeois upbringing, which is why being the first to crack open one of the Catholic filing cabinets remains so unforgettable to me. All of this produced a dizzying feeling that all of the barriers that separated us from the other classes could fall quite easily, a feeling of liberty and fraternity denied us thus far. We were increasingly convinced that impudence wins, that anything was possible; we just needed to grasp it.

But then disenchantment set in: A small group of Catholic students on Suarezstrasse had rebelled against being patronized by the Catholic administrators, kicked them out and, in order to secure their autonomy, installed new locks throughout the building. Astonished by their revolutionary verve, the diocese had no idea how to respond to this surprise attack. The students now ran the building themselves. They even attacked the cleaning women who still dutifully showed up to work with water from a fire hose. The reason they gave was that the diocese had sent the women as spies.

From now on, nobody cleaned at all: First the common kitchens became filthy, then the showers, and when vacation rolled around more and more students abandoned the squatted dormitory, which hardly seemed livable anymore. Finally, towards the end of vacation, a police operation removed the remaining squatters, who put up no resistance.

Our film about the squatted dormitory shows all of the stages of the lived utopia up to its decline, documents how the abandoned leaders dreamed their days away listening to Pink Floyd and smoking hash and, as the end approached, destroyed the building’s electrical equipment. Some weeks later I found them in a cadre party, and a few years after that in suits and ties.

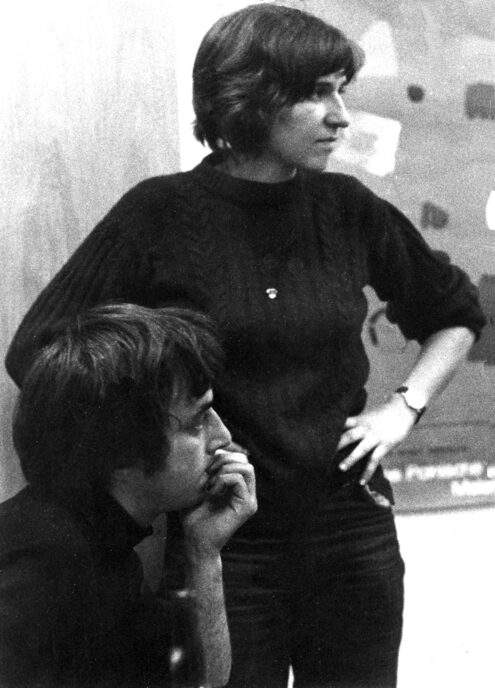

Photo: Private collection Helene Schwarz

Satansweiber von Tittfield

At this time the men at the Film Academy gave Gisela Tuchtenhagen and me the collective nickname “Satansweiber von Tittfield,” (literally Satanic Females of Tittfield) after the German title of Russ Meyer’s film Faster Pussycat Kill! Kill! Not yet so well versed in film history, we applied for a screening of the picture. We saw buxom ladies in leather murdering men with gusto! What had we done to earn this moniker?

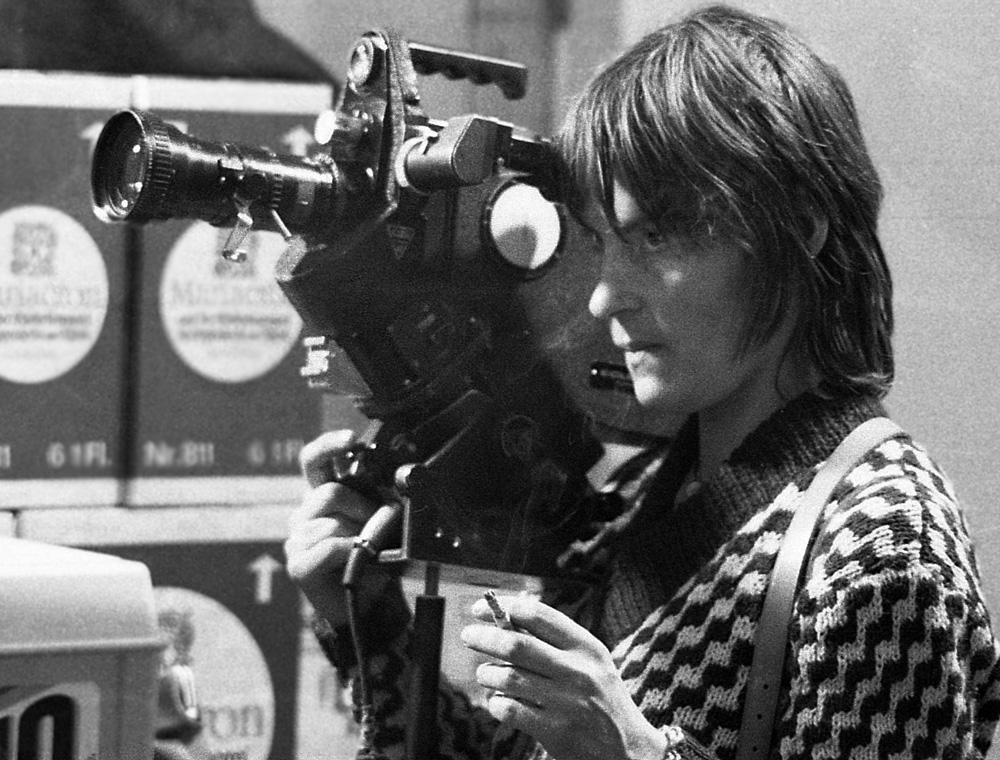

Gisela Tuchtenhagen and I proved ourselves as a team—a team of women! Women behind the camera were an unfamiliar phenomenon. Women film students were regularly tasked with managing the sound, which was neglected in those days anyway.

At first we alternated doing camera and sound for each roll of film, but I soon recognized Gisela’s outstanding gifts as a camerawoman—it was the first film she had shot herself—and decided to stick to sound and interviewing from now on. While I cluelessly panned and zoomed the camera like an amateur, Gisela held it steadily on a face, allowing the viewer to read it. Pauses, bewilderment and trivialities could not faze her, she remained focused, creating an almost magical closeness. Doing interviews had a surprise in store for me: I discovered the microphone as a magic wand that encouraged strangers to willingly bare their innermost thoughts and feelings to me.

Once removed from the omnipresent indoctrination and patronizing by theoretically adept students, we sensed that we were doing good work at the first go1. At the Film Academy, in turn, people were happy to give us their surplus raw film material. We self-confidently carried stack after stack of film rolls past our fellow students, who were paralyzed by partisan debates.

And here is another scene that illustrates how we avoided such discussions: While fellow students dutifully gathered round the instructor Sigrid Fronius in a seminar on political economy, Gisela carried me piggyback, rushing through the classroom and out again with both of us giving Indian war cries.

We then learned the hard way that we did not stand a chance in a political discussion—we simply lacked the vocabulary. It dawned on us that the documentary about the squatted dormitory should also reflect upon how our work as participant observers had changed us. That is, we wanted to emerge from behind the camera and portray ourselves as subjectively operating beings subject to influence. We immediately presented this idea to the most senior member of our group, Thomas Mitscherlich.

I cannot recall ever again being subjected to such an avalanche of invective. He was probably in the phase described above, in which leftists were becoming ruefully aware of their own boundless narcissism. He may also have been struggling with his self-imposed task of finding revolutionary potential in two public transportation employees, while Gisela and I floated from one action to the next. His particular hatred was directed at our self-assured and easygoing behavior (see “Satansweiber von Tittfield”), and in fact Gisela’s Bermuda shorts came in for special critical mention. This may provide some idea of how confused and at the mercy of his emotions even Thomas Mitscherlich was in this situation.

One year later I would have to suffer a similar rebuff by Helke Sander. She and Thomas were among the leftists at the Film Academy who had escaped the penalty of expulsion. They anxiously oriented themselves towards the working class, submitted to the “proper” line and proved it by crushing divergent but politically important and correct ideas. It was this turning our backs on our own needs that would make it so difficult for us politicized women to get the new women’s movement off the ground. Years would go by in the search.

- Our film, Wochenschau III, received the cultural prize of the federal state of North-Rhine Westphalia on the occasion of the 1970 Oberhausen Short Film Festival, along with euphoric reviews and the title “Best Film in the West German Program.” Handelsblatt, 21 April 1970. ↩