In 1998, on the thirtieth anniversary of 1968, the media showcased the spokesmen of the time: Rudi Dutschke, Bernd Rabehl, Knut Nevermann, Rainer Langhans and Horst Mahler. They accorded them hours of broadcasting time for their mainly negative assessment of 1968. The following chapters describe the 68er movement from the perspective of a woman, a first-year student from the countryside: Not from above, but from below.

The events at the German Film and Television Academy in Berlin (dffb), where I began to study in 1968, illustrate on a small scale what moved students in those days and how the ‘establishment’ reacted to them. Film technology was also taking giant strides at this time, thereby opening up new ways of working in documentary cinema. Simultaneously, a freshly awakened social consciousness discovered the medium’s political dimension and expected a politically aware use of this expensive, exclusive and powerful instrument from filmmakers. The chapters in Part 1 reflect both the political movement and the development of the medium.

The Film Academy as a Battleground

The German Film and Television Academy (dffb) in Berlin is a small, elite educational institution (with 18 students admitted per year out of 500 applications in those days), organized as a limited liability company (GmbH) responsible to the board composed of members of the Berlin Senate (city-state government) and the Federal Ministry of the Interior. In its third year of existence in 1968, it was headed by a directorate consisting of Erwin Leiser and Dr. Heinz Rathsack. They alone decided on the curriculum and appointed instructors, who at that point were still all men. The students were dissatisfied with the teaching and protested, which the directors and some instructors was unseemly and unheard-of behavior. The fronts hardened. Helene Schwarz played an important role in resolving the situation.

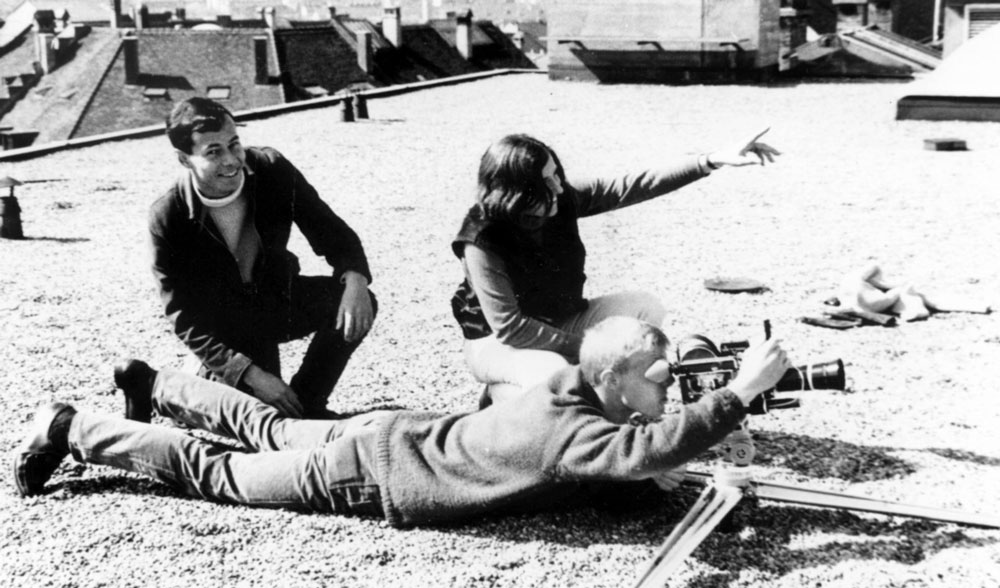

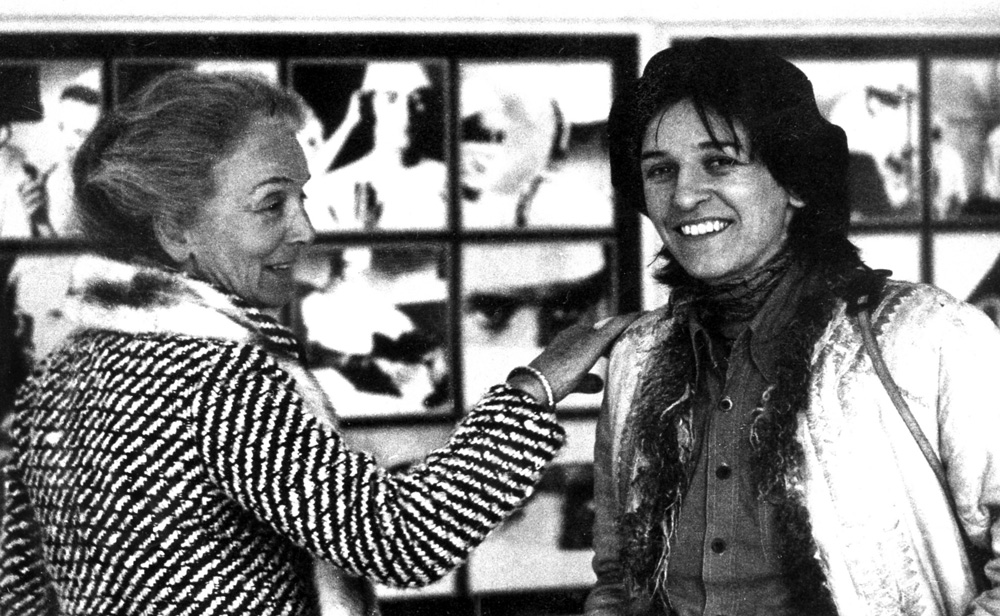

Photo: Private collection Helene Schwarz

At the time she was a secretary responsible for all of the concerns of students and instructors, since there was as yet no director of studies. She recalls:

I thought about what to do and one evening invited almost all of the instructorsto my home—the film festival was on and everybody was in Berlin: Johannes Schaaf, Christian Rischert, Michael Ballhaus, Ulrich Gregor — not the two directors, but a few students instead: Harun Farocki, Hartmut Bitomski, Holger Meins and Gerd Conradt.

There was a long discussion and the instructors warmed to the students’ ideas.

Finally, Ulrich Gregor suggested founding an academic council with one-third students, one-third instructor and one-third administrative representation. Thus the idea of one-third parity was born in my apartment, which makes me happy and proud, it was a tool that has worked very well to this day.

The instructors ultimately pushed through this suggestion, but at the same time had to prevent the dismissal of Helene Schwarz. In a sort of anticipation of later developments in higher education, she had intervened in policy as an employee of the institution. When the director Dr. Rathsack found out that this plan had been devised on her initiative he summoned her to his office and said:

“Who do you think you are, you’re nothing but a little employee

here, how dare you interfere with this policy—one-third parity, the very idea!”

He excluded me from the next instructors’ conference.

Then Michael Ballhaus asked at the beginning of the session: “Well, well, Frau Schwarz isn’t here today?”

“No, she isn’t here today.”

Then at another point Ulrich Gregor said: “I find it strange that Frau Schwarz isn’t here.”

“Well, there are reasons for that,” said Rathsack.

Then came Johannes Schaaf: “What’s up, Frau Schwarz isn’t here?”

“No, she isn’t here” and Johannes: “Is she ill?”

“No, she isn’t ill, we can do without her today.”

“Is Frau Schwarz’s job in danger?”

“No, everything is fine.”

And then Johannes said: “So, you are telling all the instructors that Frau Schwarz’s job is not in danger and everything is fine. I’m relieved to hear it, we can continue now.”

And that saved me.

A further point of conflict was the question of whom the students’ films belonged to. The film student Gunter Peter Straschek had made a film in a Berlin plant entitled “A Western for the SDS.” For whatever reason, this alarmed the political police and the Senator of the Interior pressured the directors of the dffb, who thereupon confiscated the film. In November 1968, eighteen students occupied the directors’ offices and demanded that they hand over the film. Helene Schwarz recalls the following dialogue: “Rathsack: ‘Leave this room immediately!’ ‘No, we are peaceful, but we are going to keep sitting here until we get the film.’ Leiser said, ‘Alright, then I will bow to force,’ went to the cupboard, unlocked it and called out: ‘Where is the film?’” The students didn’t believe him but assumed that he had taken it home the evening before.

The film had disappeared, but the question remained, whom do the student’s productions actually belong to? Those who financed them or those who made them? It was understandable that the directors did not want a film that explained how to manufacture a Molotov cocktail to reach the public, after all, as administrators they had to answer to the Senate of the Interior and the Ministry of the Interior. On the other hand, we had to ask ourselves, might other productions not also ‘disappear’ if they represented interests that made the government uneasy? Given the students’ radical aspiration to use the medium of film to promote the consciousness-raising of the ‘masses’ if not ‘the Revolution’, this remained a central question.

However, I am not aware of another case of censorship by the directors, though I do know of one that occurred nine years later for which students were responsible: In 1977 Helke Sander, assisted by a female film student, filmed an interview with Henning Spangenberg, one of the RAF lawyers, in which he equated the arrogant attitude of the RAF fighters with that of the Bonn government at the time. This film, The Terror Lawyer was withheld from the public by the decision of the plenary assembly of the Film Academy1.

The fact that the directors of the Berlin Film Academy were reticent with censorship may have been due to the first determined student resistance described above. After all, the students of the Munich Film School, who were considered apolitical, experienced far more massive interventions. For instance, a documentary by Sabine Eckhard using interviews with battered women was not allowed to participate in the Berlinale in 1979.

The occupation of Erwin Leiser’s office by students had massive consequences for all involved: Leiser was relieved of his position—on the grounds of protracted absence. He continued to receive his director’s salary for a further two years, however. The 18 students who had occupied the office were expelled from the Film Academy. Those who had to leave included not only some of the most engaged but also the most outstanding students such as Harun Farocki, Holger Meins, Werner (Philip) Sauber, Gerd Conradt, Hartmut Bitomski, Christian Ziewer and Max Willutzki. The expelled students later received DM 18,000 in compensation for this outrageously disproportionate punishment.

Art versus Politics

At this time I was typical of the apolitical remainder of students. I did not participate in the occupation and the strike that followed did not stop me from continuing to tinker in the cutting room. I would have made advertising films in those days to learn my craft, so exclusive was my professional orientation when I arrived at this—in the meantime highly politicized—educational institution. Indeed, after finishing secondary school I had not even turned up my nose at an internship with the Swiss Army Film Service!

I did that, however, only after having inquired about the training (in 1960s Switzerland) intended for women who aspired to be film directors: A three-year apprenticeship in a film laboratory was the prerequisite for a position as assistant editor. After a few years one might rise to the position of independent editor. Later, if one was lucky, I would be able to edit feature films and then meet a male director and then maybe… In comparison to this career path, the three-year program at the Film Academy seemed like winning the lottery, and it was too precious to waste on a strike.

To that extent, radical students regarded me as a bit stupid, a hayseed (I come from the countryside). Whenever I said something, people would cut me off: “You’ve got no consciousness.”

So, what was the nature of my ‘consciousness’ in those days? In the 1960s, the influential film directors were Antonioni, Pasolini, Fellini and Godard. Nowadays, these films are only shown in single screenings at repertory cinemas, but in their day these artistically ambitious films were simply part of the normal cinema program, at least in Switzerland. As a school pupil I was forever making pilgrimages to the movie theater with my friends, reading screenplays and attending film seminars.

Then the ‘Living Theater’ from New York came to Bern and our perspective changed spectacularly. Shortly thereafter, in 1966, I saw the first ‘underground films’ from the USA (for example by Gregory Markopolous). The Living Theater and underground films ended the diktat of the drama and the story. Sounds and images were no longer mere vehicles for conveying a message, but should be perceived as such individually. The possibility of making films without a narrative, and simply to trust in the effects of sounds and images without a ‘superstructure’ was fascinating, pure cinematic art and a liberation. In 1967 while I was still at school I made my first 16 mm film with the assistance of fellow film enthusiasts among my classmates. The leading women were my friends Billy and Verena Stefan.

Despite using only a cine-zoom camera and no editing bench, we even dubbed in language, mixed music and created an artistically and technically respectable little film. It shows a sequence of precisely composed images and scenes that are supposed to affect the viewer directly, without a story and without a message that can be expressed in words— pure film.

The War Game

After passing my secondary school exams I began an internship at the Swiss Army Film Service. Here I saw films that drove me even further into the ‘underground’. One of my duties was to screen films for military instructors, including those from the so-called poison cabinet. There was a training film, for instance, about how to respond to an atomic shock wave (always lie under the window). And another one about the wave of heat that followed. A third film instructed the troops in how to move around in an area contaminated by radiation (put on a gasmask and a tarpaulin). The officers always viewed the problems in isolation. In reality, however, the shock wave, wave of heat and contamination occurred at the same time, not separately as they did in the instructional films. And I also asked myself, where was the civilian population in all this?

At this time there was a film that showed just that: The War Game2, produced for the BBC in 1965, but banned in Switzerland. My colleague took it out of the ‘poison cabinet’ and presented it to me. She had been unable to work for days after watching it. No discussion was possible with our male colleagues, who hid behind sarcasm. Now she didn’t want to be alone with what she had seen.

The War Game is matter-of-fact, made with empathy but without sensationalism. You are constantly thinking along with the film, hoping that it is exaggerated and wishing the ground would open up so one could escape the compelling reality, before concluding that this might be what it is like to experience an atom bomb attack on the ground.

The images of this doom and gloom scenario weighed heavily. My friends felt as bewildered as I did. I did not speak about it to teachers or my parents. As a young person, they seemed to me to live in another, firmly established world, cut off from anything that could shake them up. I also knew of no anti-atomic weapons group; there was probably not a single politically active youth group in Bern in those days. All we knew of were the Girl Scouts, church youth groups and sports clubs. All that remained was to retreat into a sort of artistic processing.

Since we had nothing to do at the Army Film Service for six months, I occupied myself with leftover film footage. All it showed was military equipment in action. I used this material to teach myself various editing techniques. The products were absurd and morbid in subject matter, but aesthetically fascinating. For example, I set footage of American and Soviet bombers to distorted music and had the planes rush through the frames in ingenious editing sequences, interrupted by signals scratched into the film which flashed to the rhythm of the music, exploding mines and figures in gasmasks wandering through contaminated landscapes. Ultimately all that interested me were the movements themselves, the relationship between light and sound in time. Logically enough, my first independent production in my first year at the Film Academy would consist solely of alternating white and black frames of film. The American underground film The Flicker3 had already used this stroboscopic effect. I now wanted to investigate further using sound.

Read Marcuse!

I had, in fact, no political ‘consciousness’. How could I acquire one? I was too embarrassed to ask my fellow students. While hitchhiking a rode with a man who developed cardboard furniture, an innovative craftsman. He seemed to me the right person to ask this question, and he knew the answer: “Read Marcuse!” Then everything went very quickly.

Herbert Marcuse’s Freudian reading of art as sublimated drives made immediate sense to me. It made me think of my mother. She always retained her self-control, shaped herself and everything around her into aesthetic perfection. Later she very much resented always having put my father’s artistic ambitions before her own. And to a certain extent this applied to me as well: I, too, seemed to sublimate my sexuality in art. I therefore informed the academic council of the Film Academy that I would not be completing my light and sound project because I had now read Marcuse, which caused a good deal of amusement.

Instead I joined the newly founded Wochenschau (newsreel) group that had formed around the documentary film instructor Klaus Wildenhahn. The name Wochenschau referred to the idea of reporting on current events in Berlin from a student perspective. In fact our productions were neither current—we spent too much time discussing for that—nor especially informative, but rather poetic and polemical. It was nevertheless an opportunity to escape from a sort of autism with artistic ambitions, to acquire the craft of documentary filmmaking and learn how to discover other people’s thoughts and motivations through observation and interviews. If a rigid society, in which for example I had nobody with whom to discuss the horrors of nuclear war, had driven me thus far to the art underground, the fresh wind of the 68ers now gave me hope. Nothing need stay the way it is, all questions are permitted. And so I now began to explore reality with enthusiasm.

- Helke Sander (ed.), Frauen und Film, no. 18 (1978): 3–13. ↩

- The War Game by Peter Watkins, a film made for BBC in 1965 in the style of a television report. The War Game was shown on German television in the 1990s. In the 1980s, Hollywood produced the blockbuster The Day After, which showed the aftermath of a nuclear bomb attack on a city in the style of a pedestrian disaster movie. ↩

- Tony Conrad, 1966, USA. ↩