Instead of a position paper we learn together

We initiated the HAW lesbian group in the winter of 1971–72 and by the summer we found ourselves stuck between cozy sociability and theoretical ambitions. As a result, I and some other lesbians felt the urge to move the feminist cause forward. In November 1972 Waltraut Siepert—my girlfriend at the time— and I placed an announcement in the magazine Hundert Blumen (Hundred Flowers), the successor to Agit 883, calling on women to come together at the Socialist Center on Stefanstrasse in the district of Moabit to found a women’s center.

As she recalled in our interview, Cornelia Mansfeld was enthusiastic about our idea:

We found the appeal in Hundert Blumen, an alternative magazine. The appeal went through the various little groups like a whisper race and it was obvious that we would be there. We wanted women to organize as women. So about 70 women from various informal contexts attended the first meeting.

I remember that first evening as incredibly exciting. I had never seen so many women together in a room without men trying to structure everything.

The first thing we did was arrange plenary meetings and subgroups, all of this done standing up because there were so many of us, and from then on we were ready to work. We simply skipped the step of a theoretical platform, which was a must in other groups. Even before this meeting there was a consensus, so that we didn’t need a lot of discussion, because all of us had the same experience with left-wing groups behind us.

Unlike other political groups, the Berlin women’s center’s first public self-presentation was not a position paper, but simply an unpretentious description of the organizational form and the contents of our work. This was accompanied, however, by a declaration of disassociation that may seem surprising today, but which was necessary at the time:

In November [19]72 a number of women came together through an advertisement. We all wanted to do work for women, but were seeking an alternative to the Socialist Women’s League of West Berlin (SFB). The SFB is inimical to praxis, hierarchical and oriented towards the SEW,[i] bureaucratic and anti-feminist. We immediately formed the first working groups: university, sexuality, early childhood education and consciousness-raising groups. In March [19]73 we had finally rented premises for a women’s center where we could counsel women, sell books and hold group meetings.

All of the women from the subgroups attend the weekly plenary. There they share their experiences from the groups and everybody discusses and decides on actions proposed by the subgroups. In this way we are constantly and collectively developing the women’s centers’ self-understanding. We therefore do not have any written positions, but are learning together.

Every Thursday delegates from every working group come to the office group, where we deal with organizational matters and conduct a preliminary discussion of pending issues for the plenary. Afterwards, at 8 pm, there is an information event for newcomers every week.

We do not side with any political party, but we support the work of the neighborhood committees, “Rote Hilfe” and the gay women. For example: On May 1 there were three different demonstrations in Berlin. We did not support any of the competing parties, but on that day we occupied a square – Richardplatz in Neukölln – for a children’s festival together with the neighborhood committee.[1]

In 1974, Anja Jovic described her experience in the Berlin women’s center as follows:

What became clear to me that first evening was that the women at the center had not already worked out some fixed theory that they wanted to impose on us, but rather immediately took us “newcomers” seriously just as we were, with our own experiences.[ii]

Decision-making structures

Every group at the Berlin women’s center was autonomous and could choose whatever field they wished to work in. The plenary never tried to regiment the groups. Any group or individual could propose actions or new groups, and they were welcome to realize their ideas as long as they could find enough people to help them. There was thus no thematic let alone political “line” that determined whether an enterprise was right and permissible. Not having to follow a line also had the advantage of flexibility. In this way, quite in keeping with our first position paper cited above, we “constantly and collectively developed the women’s center’s self-understanding. We therefore do not have a self-understanding on paper, but are learning together.”

Helga Pahl, a technical draftswoman and married at the time, characterized the structures at the women’s center as follows in an interview:

We didn’t really think so much in terms of structure; that had its good sides, because it meant that people who weren’t used to opening their mouths dared to speak up. After all, the students were all better talkers.

– I had the feeling that people listened to one another, so that even ordinary housewives felt they could express their opinions.

– In order to avoid having to start at square one every time, we founded the newcomers’ plenary, where we introduced ourselves and the new women could integrate into the groups, then things were fine.

– Yes, enjoyably chaotic; things sorted themselves out.

– Very little structure was needed for things to work.

– Yes, when I look at the work I do now, where everything is supposed to be pressed into a mold…

In conversation, Roswitha Burgard confirmed the absence of ideology at the women’s center:

What I [Cristina Perincioli] find amazing is that we never had a discussion at the women’s center about the proper line to take. The women came from different contexts, anarchists, lesbians, PL/PI, Rote Hilfe etc and everybody immediately agreed about what the center should be like. I cannot recall any discussions about the proper line. And I think that applied to some of the women’s centers in other cities as well. How do you remember that?

– Yes, that’s true. But there was also a general mood of optimism and change…

– At the Film Academy and probably at the Institute of Psychology where you studied too the students were feuding day and night over who was right.

– But we argued at the women’s center too!

– yes, but it was never about using your knowledge to impress others, though, and we never had abstract ideological discussions.

Where had all of this unanimity come from all of a sudden, considering the constant disputes on the Action Council for the Liberation of Women? How can it be explained? I believe there were three new political principles behind this difference. As far as I know, the women’s movement was the first political movement to put these principles into practice:

Our principles

- Immediacy

The women dispensed with knowing the right path to revolution, or rather with aspirations to revolution altogether. They simply wanted to tackle the issues that got them fired up. These were very diverse areas, but it was always about the desire to make changes that could be expressed directly, and that in some cases were also attainable. There were groups working on the situation of women at Berlin’s universities and teacher training college (PH); women working in early childhood education also had their own professional group. There was a sexuality group, consciousness-raising (CR) groups, a prison group, a media group and of course a §218 group, which did abortion counseling, organized trips to Holland and campaigned against the law. All of these groups did both theoretical and practical work and engaged in self-reflection. Strategy discussions were based solely on our own successes or failures and not on nineteenth-century texts, as was usual in the Socialist Women’s League of West Berlin (SFB) and the other dogmatic leftist groups.

- Taking ourselves seriously

For all those women who had been living and thinking in leftist settings and who had repeatedly seen their most pressing problems dismissed as trivial and apolitical, it was a huge relief to finally engage in political work with which they could identify fully, and they defended this realization fiercely from then on. Anja Jovic described this evolution as follows in 1974:

I didn’t see the necessity to go to a women’s group. After all, I had everything, my studies, my independence (?), my birth control pill, my relationships. Only when I was reading Kate Millet or someone like that did I feel a cold rage. My boyfriend said, “You should know that those are merely versions of the basic contradiction.” I was furious: Once again it wasn’t about me, since I wasn’t a wage laborer. But why the hell did I feel so awful?[iii]

The plenary at the women’s center became incredibly important for me emotionally. For the first time I saw women taking themselves seriously, making themselves the subject of political practice, having the guts to make demands on their own behalf without hiding behind the working class. Usually people talked about medical problems, about §218, and many of my own difficulties, which I had never realized were political, related to that.

All those individual, humiliating experiences with gynecologists with their series of recommendations for an inflammation of the ovaries that I probably never even had: hospitalization, sexual abstinence and immediate pregnancy, all these experiences—slaps on the behind, paternal grins, assembly-line treatment—coalesced into a system of violence that had had no place in my “revolutionary consciousness.[iv]”

- Autonomy

We furiously resisted the attempts of dogmatic groups to co-opt us for particular occasions, and were extremely circumspect about cooperating with party organizations. For example, the Communist League of West Germany (KBW) also demanded a place at a demonstration against §218. In laborious negotiations, we agreed on a series of slogans that would not consist solely of KBW self-promotion. I carried a set of pliers with me just in case they violated the agreement and I had to put their loudspeakers out of commission. We knew from experience that communist organizations like to ride the coattails of popular movements, making the events look like their own by having the more powerful loudspeakers. The persistence of our distaste for dogmatic groups is evident from an August 1978 note in the magazine Courage:

In early June—to the horror of all “old” women’s center women— the Socialist Women’s League of West Berlin (SFB) met in the plenary room at Stresemannstrasse 40. Ten center women hastily assembled by telephone managed to clarify that this was a one-time visit made possible by ignorance of the groups’ differences.

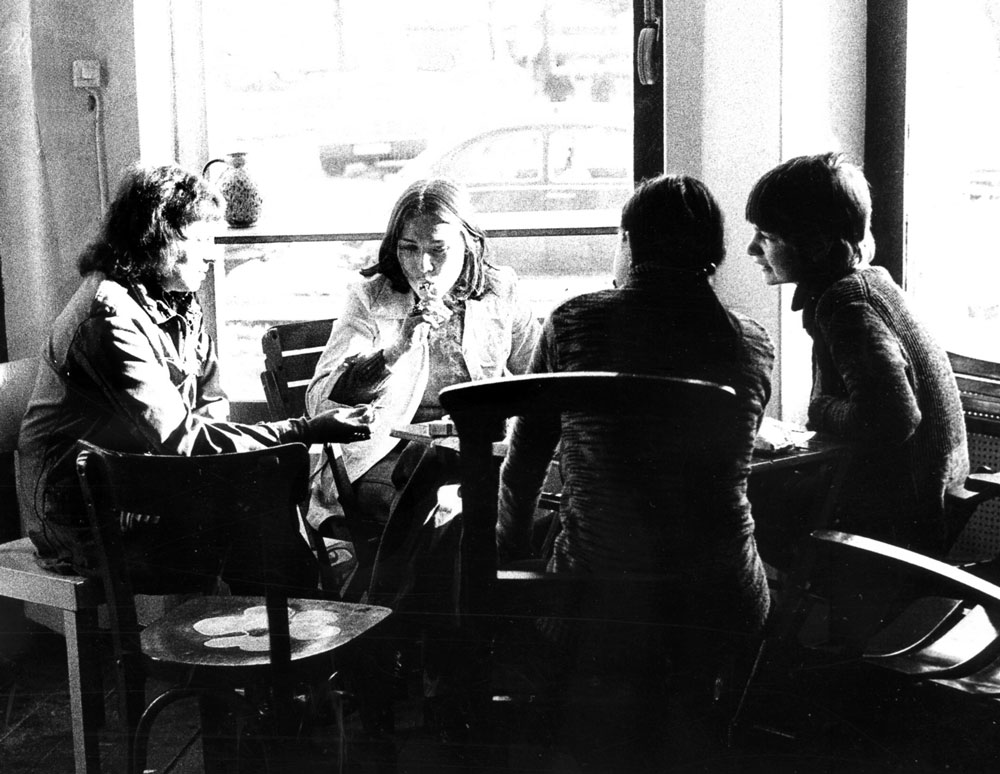

From 1973 to 1976 the women’s center was located in this former potato shop at Hornstrasse 2 at the corner of Yorckstrasse. The miserable state of the façade did not stand out at the time, since the renovation of prewar buildings in Kreuzberg began only in the 1980s. We paid the rent out of our own pockets: Each member contributed between 10 and 20 DM a month. Photo: Anke-Rixa Hansen

Was it truly a grassroots democracy?

Beatrice E. Stammer was a high school student when she first came to the center. She addressed this question in retrospect in an interview:

I know that there were endless discussions about many matters, we didn’t just vote. Sometimes we sat there until two in the morning, we were always supposed to reach a consensus. That was great because we learned how to use arguments. There were only a few people who did things differently, like Alice Schwarzer.

I encountered more rigid structures among the anarchist women. The more radical somebody was, the more she had to say. There was insane pressure to always do an action right away with no chance for discussion. We were often out and about at night from the women’s center too, but I always felt like I was in good hands with those women.

The center after one year, in autumn 1974

In an article that Cillie Rentmeister and I wrote for a US publication in 1974[v] we mention 24 working groups on the following topics:

4 Consciousness-raising

4 Self-help

2 Abortion counseling and campaigning against §218

2 Sexuality, Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm

University group: Seminars on the women’s situation as students and instructors

3 Theories of the women’s movement, including August Bebel, Friedrich Engels, Selma James

1 Wages for Housework (Mariarosa Dalla Costa)

1 Rape, self-defense course with 25 women from the center

Occupational groups with women employed in:

The media

The health professions

Psychotherapy, psychiatric hospitals

Art history

The schools

1 group of psychologists and sociologists is preparing the groundwork for a women’s counseling center for educational, legal and medical questions

1 women’s rock band Flying Lesbians, which occasionally drives women wild, especially because women’s parties quickly become very popular.

[1] Document in the archive C. Rentmeister

[i] The Socialist Unity Party of West Berlin (SEW) was the West Berlin branch of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) in the GDR.

[ii] Anja Jovic, “Ich war getrennt von mir selbst…” Kursbuch 37, “Verkehrsformen,” vol. 2: Emanzipation in der Gruppe und die “Kosten” der Solidarität (Berlin, 1974), 67–83, 75.

[iii] Jovic, “Ich war getrennt,” p. 74.

[iv] Jovic, p. 76.

[v] Cillie Rentmeister and Cristina Perincioli, “Berlin, Women in Two Different Systems” (1974). There is a summary in the chapter Over the Berlin Wall