Trips to Holland/ Vacuum Aspiration Method/ Modernizing Gynecology /Civil Disobedience / Self-examination/ Feminist Health Center

In a 1971 action in which women publicly admitted to having had an abortion, Alice Schwarzer had already mobilized against the German abortion ban in collaboration with the Stern news magazine.[i] The Socialist Women’s League of West Berlin (SFB) also opposed the anti-abortion law §218 as a “class law.” This outrage over the law did not lead to any concrete structures, however. Nothing had improved for women, beyond greater awareness in society. Only the women’s centers could offer concrete help to women who needed abortions. For that reason, abortion counseling was one of the most important tasks for women’s centers in the early years.

Trips to Holland

Beate Kortendieck, now a gynecologist, recalls

When we began our counseling work at the women’s center, we compiled a list of Dutch abortion clinics, visited them and organized trips there. Many women also came to Berlin from West Germany because it was the only place they could get help. We wanted to push through the right to abortion, but I didn’t yet think about the emotional implications at the time. Our counseling was also not comparable to what exists today. The only legal option at the time was the medical indication. That meant that the woman had to see two psychiatrists and convince them she was severely depressed. We told the women what they had to say to the psychiatrists. There was one doctor in Berlin who then performed the legal termination, and a number of doctors who did it illegally and charged accordingly.

Cornelia Mansfeld drove the women to the Dutch clinics in an unheated bus:

What we were doing was illegal, so we didn’t shout it from the rooftops. We always did our planning on the playground outside the women’s center to make sure that nobody was listening in.

Beatrice E. Stammer was studying art education and is now a curator in Berlin:

I got involved in the abortion rights group because I had an abortion myself in 1973. We did lots of illegal trips to Holland up to 1974, when the law was changed. I was in Groningen six or seven times. We drove in my orange VW bug; I was only 19 and had just gotten my driver’s license, so two of us shared the driving. There was a brief discussion beforehand, then the termination was performed and the woman could lie down for fifteen minutes. They did the procedures at fifteen-minute intervals. Feminists from many countries came together there.

The women made a donation to the women’s center of between 20 and 50 marks and we shared the cost of gas. The women’s center organized a bus to Holland every two weeks and we made extra trips in between as well.

It wasn’t just social work—we got something out of these trips too. We met women from all over Europe, there was a lively international exchange— it was a heady experience: You had friends and acquaintances everywhere, and felt at home everywhere, whether in Groningen, Amsterdam or Cologne. We encountered warmth and affection everywhere, and people were always willing to put us up for the night.

Curettage, prostaglandin, vacuum aspiration

The most common abortion method at the time was dilation and curettage, which had to be done under general anesthetic and also had a high risk of injury with negative effects if the woman hoped to become pregnant again in future. “At the Göttingen University clinic, then-director Professor Heinz Kirchhoff, an opponent of legalizing abortion in the first trimester, noted a complication rate of 30 percent for 340 (legal) procedures. Apart from the perforation of the uterine wall by medical instruments, the most feared complication was the life-threatening blood loss that occurred from time to time.”[ii]

A new abortion method was being tested at the time, the use of prostaglandin to induce labor and cause a “miscarriage.” This method had been little researched at the time, had severe side-effects and was extremely painful. It seems that in some hospitals women were subjected to this procedure without being properly informed beforehand, possibly for experimental purposes.[iii]

In the meantime, the US psychologist Harvey Karman had developed the aspiration method. In this method, the cervix was dilated just enough to introduce a four-millimeter suction tube into the uterus. Under local anesthetic, the abortion could be performed in a few minutes and the woman could go home right afterwards. By 1971, 60 percent of abortions in New York were already being performed by this method. It was even adopted in the GDR. Statistics from Dresden show that the rate of complications fell from 15 to 5 percent as a result.[iv] The officials of medical associations in the Federal Republic, however, resisted the introduction of this method. This resistance and the use of prostaglandin reinforced our suspicions that gynecologists were not interested in women’s wellbeing, but rather wanted abortion to remain dangerous and painful.

As a doctor in training, Beate Kortendieck did abortion counseling at the women’s center. She acquired her information first-hand:

In order to learn the (Karman) aspiration method myself, I spent four weeks working in an abortion clinic in Holland. Then we traveled to Paris, where they instructed us in an astoundingly simple technique that actually made it possible to perform abortions in the kitchen using a bicycle pump with an inverted valve. Brilliant! Of course they used sterile tubes and cannulas and plastic dilators. Here we saw how women in the neighborhood took things in hand themselves.

Cornelia Mansfeld:

About 20 women worked in this group. But we also experimented a lot ourselves; one of us had herself sterilized—at the age of 25. She contracted septicemia at the clinic and almost died because the doctor didn’t care.

Another one managed to get an abortion at the Klinikum Steglitz, which had refused up until then. And they promptly left something inside her and couldn’t perform a medically proper abortion.

We used our own bodies, as it were, to enforce our political claims, risking our own health. We must have been very estranged from our own bodies. It was a bit crazy, and we took many things too lightly.

“We have the choice between arsenic and strychnine,” we used to say. Birth control pills were still total hormone bombs, and many women found IUDs painful. We also tried the temperature method, but immediately became pregnant, and condoms were rejected as an imposition: rubber instead of body contact. On the other hand, they were also a test for the man, of whether he was willing to take responsibility.

Before the advent of the Pill, our mothers had been even more dependent on male benevolence; they could be impregnated against their will. This problem disappeared with the Pill, but at the same time women were subject to a “new availability.”

We described our counseling work in the First Women’s Yearbook.[v] Most women only wanted addresses from us and we never saw them again. But we wanted them to recognize their shared experience, which is why we switched to group counseling in which they took turns telling their stories and we explained our principles and gave each one specific advice. First she needed a doctor to supply the indication and then one to perform a legal, reliable abortion. For that reason we collected the addresses of good gynecologists. We only traveled to Holland later.

After Alice Schwarzer’s TV program on NDR (North German Broadcasting) in 1974 there was such a rush of interest that we had to offer counseling every day. Women even came from West Germany. I can remember endless organizational work, and we quickly turned into a service provider.

Later a group split off and founded the Feminist Women’s Health Center (FFGZ).

Civil disobedience: An abortion on television

Alice Schwarzer had already unleashed a campaign against the abortion ban with her 1971 Stern title story “We Had an Abortion.” In 1974, she tried to accelerate the conflict over abortion law with a self-incrimination by abortion doctors. At the same time, she wanted to promote the aspiration method and show an abortion using it on the television news magazine Panorama, pushing ahead the debate with this provocative, very public violation of the law. It required the kind of energy typical of Alice Schwarzer to persuade 329 doctors to admit publicly to having performed abortions and to find a woman willing to terminate her pregnancy on camera as well as the doctors to do the procedure.

The entire action was planned with military precision. Alice entrusted me with the publicity work, i.e., she showed me how a professional press campaign should be run in the first place. I was merely a cog in the wheel, but it gave me my first opportunity to learn from an experienced woman, since in those days feminist groups operated according to the principle that everybody did everything, and we often paid for this equality within the group with dilettantism in the execution.

Then the day came when the abortion was supposed to be filmed. Alice decided that I should operate one of the NDR cameras. The film team was brought to the scene of the crime in such a way that we didn’t recognize the street, which proved to be a wise idea in the end.[vi] We also were not allowed to see the participating doctors or the patient except with wigs and glasses, so that we couldn’t identify them later. The abortion by the vacuum aspiration method itself took five minutes and went so smoothly that the woman involved could go to the theater that same evening.

I was incredibly glad that the coup had succeeded so professionally and effectively. It was a spectacular new experience for me. The actions I had done together with anarchist women had demanded courage and toughness alone; they were consistently destructive but entailed little political success for incalculable risk. This was a new tactic: The ostentatious, publicly documented violation of a law that millions of women had broken thus far, only in secret and under undignified circumstances.

Photo: Cristina Perincioli

Broadcasting freedom came under fire as never before. Cardinal Julius Döpfner threatened to bring criminal charges against North German Broadcasting because the film segment represented a “call to break the law.” The influence of the churches on the broadcasting councils was so massive that seven of nine ARD broadcasting stations refused to air the film. Franz Barsig, the director of Sender Freies Berlin (SFB), had demanded that NDR show gory footage of the curettage of a five-month-old fetus in addition to the aspiration method. When NDR refused, he, too, withdrew his consent to the program two hours before it was due to be broadcast on 11. März 1974.

The press had been reporting on the conflict within ARD for days, so that half the country was sitting in front of their TVs. The Panorama producers were forbidden to air the segment, but instead of replacing it with another as they usually did, they had a protest statement read out and broadcast the image of their empty studio. An entire television program visibly on strike was something unprecedented.

Sit-in at the television station

Unhindered by the hierarchies and formal decision-making procedures that paralyzed other organizations—such as the Socialist Women’s League of West Berlin (SFB)— at the women’s center anyone could spontaneously initiate an action. Those that did not attract sufficient interest simply never got off the ground. On the morning after the non-broadcast of the abortion film 60 women appeared outside the studios of Sender Freies Berlin (SFB). Just to be on the safe side, we assembled out of sight of the porter’s lodge and then together stormed the barrier into the building. Through our publicity work we already knew a few women who worked there who could tell us where the director was at that moment. We flocked there and beset him so massively that, according to the magazine Spiegel, he even ended up with bruises. In any case he immediately called a public meeting in the SFB conference room that many staff members attended. This caught us unprepared and we didn’t know how to grasp the opportunity. We ended up listening quietly to his explanations and then leaving, our only success the fact that we had been noticed at all.

A sit-in we organized at the conservative medical association ended just as unsatisfactorily for us. We had just occupied the hall and Helke Sander had barely begun her speech when somebody turned off the microphone. Helke had not informed us of what she intended to say, but had merely enlisted the women’s center as a mass of supporters. Deprived of any agency, we could only beat a retreat.

Struggling for a woman-friendly gynecology

Helke Sander had already founded the group Brot und Rosen (Bread and Roses) in 1971 to investigate the side effects of the Pill and the practices of gynecologists, which led to the compiling of the Handbook for Women No. 1. The work of this group was results-oriented but not grassroots democratic, as Beate Kortendieck discovered:

Our motto at the women’s center and also in the neighborhood groups was: The people affected must organize themselves and define their own goals and politics, not base them on some theory or other. This grassroots democratic concept also set us apart from Brot und Rosen.

Originally I didn’t want anything to do with obstetrics, but because of the abortion rights group I did my residency in gynecology. It was a very tough time because the profession was dominated by men and their terrible image of women, starting with the nasty jokes that doctors told in the operating room. It was horrible in those days, very hard to bear!

Afterwards I got a permanent position, but only on the condition that I didn’t have any children. I quit after two years; I couldn’t stand it any more.

During our conversation I asked her for concrete examples from gynecological practice:

When I started working in gynecology women were still strapped onto their beds. We had lots of Turkish patients when I worked in Berlin‘s Wedding district. They frequently retained a natural attitude towards childbirth and quite rightly resisted giving birth on their backs. But we had to monitor the heartbeats, so the women’s arms and legs were strapped down. It was awful. It was also usual to hold the babies up by their legs to be able to measure them better, and to slap them. Measuring and monitoring were the most important things. The notion of the arrival of a human being who needed to be welcomed was not part of medical consciousness. As a result of the women’s movement there were many more committed women working in the hospitals who began to make changes.

With the nuns

The desire of pregnant women to give birth under more humane conditions eventually led to a return to traditional midwifery, according to Beate Kortendieck:

A few years later—I had now given birth at home myself—I went to St. Gertraude hospital, which was run by nuns, who still practiced an old-fashioned form of obstetrics. The effect of this, combined with new ideas from the women’s movement, was that now all the women went to St. Gertraude to give birth, because they used quite natural methods there. It was only this circumstance that brought about changes at other hospitals, not because they started thinking in new ways, but because they saw that they were losing their patients to “Gertraude.” For economic reasons they now began to move away from programmed births with thousands of controls and to be more accommodating towards women. These changes were most certainly a success of the women’s movement, of the wider women’s movement, but these topics were then also discussed in women’s and parents’ magazines.

Self-examination

Dagmar Schultz had studied in the USA and brought her experiences in the American women’s movement to the Berlin women’s center. The book Our Bodies, Ourselves,[viii] in particular, was translated right away. The German edition of Our Bodies, Ourselves did more than just supplement what Brot und Rosen had begun in 1972 in their Frauenhandbuch Nr. 1: the critical examination of gynecologists and their frequently misogynist techniques. It also encouraged women to acquire their own knowledge of the workings of the female sexual organs in order not to be at the mercy of the medical profession any more. In fact we had never looked at our own genitals, didn’t know how they worked or looked, how their appearance changed and what this meant. We had always left this up to gynecologists, and with it decisions about our health and wellbeing. We intended to take back this terrain.

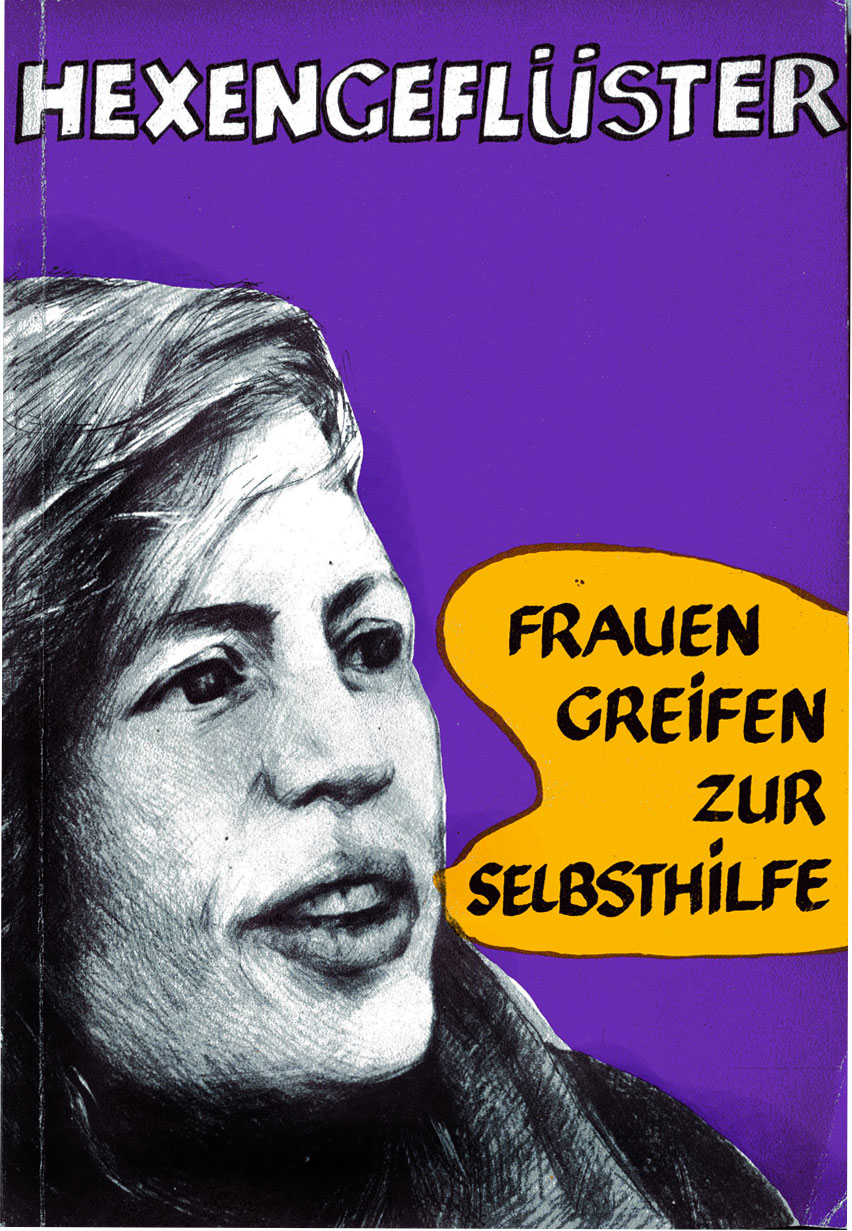

Gaby Karsten explained this to us one day at the women’s center and proceeded to undress “down there,” lie down on a table in front of the plenary and insert a speculum into her vagina so that all of us could see how easy the procedure was. This scene took my breath away, but Gaby broke through our embarrassment by acting as if this were the most natural thing in the world. She was fired by the will to liberation. From now on, everything behind our “pubic triangle” was subject to investigation and discussion. After this demonstration we formed about 20 groups who examined themselves in the same way. In 1974 one group founded the Feminist Women’s Health Center (FFGZ), which still exists today. That same year group members Dagmar Schultz, Gaby Karsten and Christiane Ewert published the handbook Hexengeflüster, which conveyed experiences and gynecological information in such a clear manner that it went through numerous editions.

[i] “We’ve had abortions,” 374 women claimed publicly and incriminated themselves as violators of existing abortion law. Of them, 28 appeared with photos on the cover of the June 6, 1971 number of Stern magazine, including Carola Stern, Romy Schneider, Senta Berger, Sabine Sinjen, Vera Tschechowa and Veruschka von Lehndorff.

[ii] Der Spiegel, April 1974, p. 21.

[iii] For women today, the further development of prostaglandin, in combination with the “abortion pill,” has made possible a simple means of terminating pregnancy with relatively few complications.

[iv] Der Spiegel, April 1974, p. 21.

[v] Frankfurter Frauen (eds), 1. Frauenjahrbuch (Frankfurt am Main, 1975).

[vi] In fact I was called as a witness a short while later. The investigating prosecutor seemed relieved that I had no idea of either the place where the abortion had occurred or of the persons involved. The politically controversial case was dropped.

[vii] Brot und Rosen, a group founded by Helke Sander, compiled the First Women’s Handbook and participated in abortion counseling at the women’s center. For more see the chapter Bread and Roses.

[viii] Our Bodies, Ourselves appeared in 9 editions beginning in 1971. It was compiled by the Boston Women’s Health Collective.