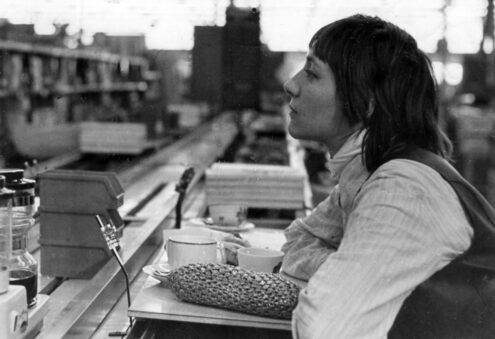

Inventing the Kinderladen/ Speech at the SDS congress in Frankfurt in ’68/ The famous tomato toss

Photo: Private collection

Inventing the Kinderladen

There is a story behind Helke Sander’s famous speech, as I found out during a conversation with her in 2014. I asked her

– People say that you invented the Kinderladen Is that how you see it?

– Oh yes, you could say that. In the summer of ’67 I put up a note at the SDS center looking for other mothers with small children who were interested in starting a reciprocal childcare network. I was familiar with the idea of “park aunties” from Scandinavia, similar to what we now call Tagesmutter (a woman who provides daycare in her own home). You could drop the kids off at the park with another woman from 9 to 11 am, for example. But everybody made fun of my idea, there wasn’t a single positive response!Within the Springer campaign there were 40 working groups on all sorts of topics, but not one on women. Reading the Springer newspapers I had noticed that they also addressed women specifically. So I felt pretty shaky when I went to our working group [Cosimaplatz 2] at Peter Schneider’s, who wasn’t as intimidating as the other big lefties. After two hours I finally asked the group whether we might not start a working group on the topic of Springer and women. Everybody was just smirking away, but Peter Schneider said, “Go see Marianne Herzog in the kitchen, things like that interest her too.”

I discussed my idea of the “park aunties” with Marianne, something that cost no money, but gave us [women] the opportunity to participate. Marianne called up Dorothea Ridder and we three spent the evening in the kitchen at Cosimaplatz 2 writing the appeal for our first meeting. That was in early December 1967. We distributed these five hundred flyers to women only.

About 100 women and a few men attended the first meeting in January 1968. The three of us had no experience with public speaking, so we were very nervous. In order to put the idea into practice we needed rooms near our own apartments. The local corner grocery stores seemed logical choices, since lots of them were vacant. The women immediately organized themselves by neighborhood and after two hours we had a plan.

The first five Kinderläden were founded that evening.

One month later, during the Vietnam Congress, we set up a room at the Technical University where children could be looked after, and asked men or fathers to run it. They then quickly founded the Central Council of Anti-Authoritarian Daycare Centers and took over the whole movement.

Up to that time it had been unthinkable for men to push baby carriages, and now they were promoting anti-authoritarian childrearing, and for some of them the Central Council was a place where they finally had a say in things.

The women, in contrast, had founded the Kinderläden to take some of the burden off themselves and to move childrearing in a new direction overall. The initial focus was not “anti-authoritarian.” In the early decades, the books and films[i] on the subject were all written by men; the women had no time, but now they had even more to do, what with all the meetings and debates on principles that the men demanded.

Speaking at the SDS Conference

Helke Sander gave her speech as a representative of the Action Council for the Liberation of Women at the 23rd conference of delegates of the Socialist German Student League in Frankfurt am Main in September 1968. It would become highly important for the women’s movement in Germany:[ii]

We will try to explain our positions; we demand a substantive discussion of our issues here. We will no longer be satisfied with women being allowed to say a word now and then, which anti-authoritarian men feel obliged to listen to only to return to business as usual.

We note that within the organization, the SDS mirrors overall conditions in society. Efforts are made to avoid anything that could contribute to articulating this conflict between aspiration and reality, since this would require a reorientation of SDS policy. This articulation is avoided in a simple way, namely, by separating a certain realm of life from the societal, imposing a taboo on it by calling it private life. In imposing a taboo the SDS is no different from the unions and the existing parties.

This taboo leads to a suppression of the specific conditions of exploitation to which women are subject, which guarantees that men do not yet need to give up their old identity bestowed upon them by patriarchy.

… In this process, the man assumes the objective role of the exploiter or class enemy, which he of course subjectively does not want, since it is in turn merely imposed on him by an achievement-oriented society that forces him into a certain role.

The consequence for the Action Council for the Liberation of Women is as follows: We cannot resolve the societal oppression of women on an individual basis. We cannot wait until after the revolution, since a revolution in political economy alone does not end the suppression of private life, as the situation in all of the socialist countries demonstrates.

We aspire to living conditions that abolish the competitive relationship between man and woman. This is possible only with a transformation of the relations of production and thus of power relations in order to create a democratic society.

Male comrades usurp the grassroot project

In what follows, Helke Sander speaks of the incredible appeal of the Kinderläden, and the current attempts of some male comrades to usurp these successful grassroots projects for their own ends:

It is particularly men, who have gradually been joining us, who argue that we need to branch out into the working class more quickly. There are two problems with this. First of all, various men have noticed that we are suddenly doing something that has a future. Because they are more skilled at speaking they assume the leadership in some working groups, and many women are still helpless to stop them. They act as if the idea for the Kinderläden was theirs, they see the political relevance and now they are telling women that they are repressing their own problems if they concern themselves with childrearing.

In fact, within a few months men had wrested these successful grassroots projects away from women; they even barred some women from the Action Council from entering the premises.

The attempt to favor other social strata with our Kinderläden as quickly as possible can perhaps be attributed to the fact that the men continue to refuse to articulate their own conflicts. At the moment, we have nothing to offer the working class. We cannot put working-class kids in our Kinderläden where they learn to act in ways that will get them punished at home. The preconditions for the workers need to be created first.

Here we already see what would become typical in subsequent years. Scarcely had a group somewhere formed on the basis of their own needs when left-wing strategists tried to place themselves at the head of this “potential” and the movement at the service of the proletariat. After all, in the moral thinking of the Left anything that did not directly benefit the class struggle was considered ‘bourgeois’ and thus egotistical.

Pointless intolerance

In the final portion of her speech, Helke Sander asks about priorities:

Should this group here or that group there concentrate on administrative offices for apprentices or school pupils, or should we focus on broadening the base of the kindergardens?

She answers her own question by presenting these secondary school pupils and apprentices as already privileged, or already twisted by the wrong upbringing. Then she also casts doubt on the relevance of other groups altogether:

Should one group mount a NATO campaign and another a Bundeswehr campaign, or should we focus on the areas of society that are pivotal for perpetuating power structures?

By denigrating other approaches this way, Helke Sander was following the usual thinking in those days, namely that there was only one true path, and missing it meant missing the revolution. The fact that leftists accepted nothing but their own party and their own sphere of influence—this pointless intolerance, which Helke Sander shared with the Left—would later force the Berlin women’s center to engage in endless discussions of justifications that obstructed everything.

To give such a speech before a body like the SDS shows historic courage! Predictably, the conference chairman did not address the questions raised by her speech, but merely proceeded to the next agenda item. At that point a woman—Sigrid Damm-Rüger—started throwing tomatoes at him. She had them with her because she had just been shopping. Since then, these tomatoes have been considered the first declaration of the new women’s movement, because for many SDS women, this was the moment when they realized how oppressed they were in the SDS.

[i] An exception is Susanne Beyeler’s film “Erziehung zum Untertan” (Education for Subservience).

[ii] Helke Sander, “Rede des Aktionsrats zur Befreiung der Frauen,” in Eckhard Siepmann (ed.), Heiß und Kalt. Die Jahre 1945 – 69. Das BilderLesebuch, 4th edn (Berlin, 1986; Berlin, 1993), pp. 625–27.