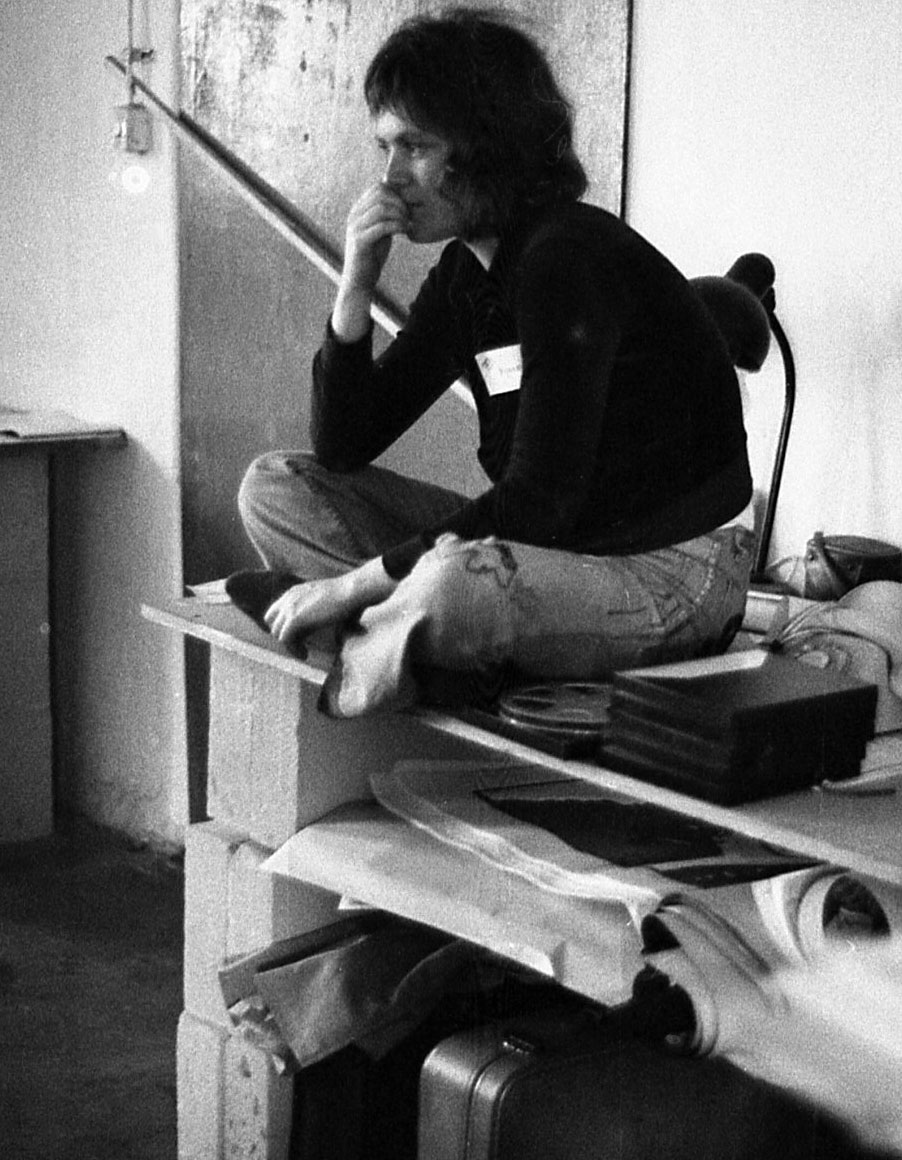

The lesbian group’s greatest impact came with the documentary film … and we take our rights, which Claus-Ferdinand Siegfried made for WDR television together with some women from HAW, a film that was broadcast during prime time on the first program of ARD and received a good deal of attention in all the print media.

In order to demonstrate that it was impossible for many lesbians to show themselves publicly, Monne Kühn appeared in the film disguised with a symbolic eye mask, but still recognizable. But what happened afterwards…

…was the breakthrough! We received laundry baskets of letters—which we answered by initiating groups in West Germany from Berlin. We asked, “Are you prepared to act as a contact?” And then we referred women who lived nearby to that woman… so they could meet in their own towns. This correspondence—without computers in those days—was done in our one-room apartment, with boxes full of letters under the bed. Very basic work. And we were in constant contact with these new groups in West Germany and more came to every Pfingsttreffen. The groups bolstered lesbians’ sense of self-worth and politicized them to some extent, so that they could be present in public as lesbians.

For me, the political dimension of HAW/LAZ was that we had brought the topic of lesbians into the public sphere with the phrase “the personal is political” and our critique of compulsory heterosexuality and inspired other lesbians, as well as a large chunk of the population, to rethink the narrow definition of normality. If broad segments of society today have developed a different and positive attitude towards lesbians, our actions and demands provided the impetus.

Whether with or without theory, Berlin lesbians made it possible through their organizational work—initiating all of these lesbian groups and the annual Pfingsttreffen—for the thousands of bewildered and oppressed women in West Germany to come out of their niches, celebrate their shared experience and draw strength and self-confidence.

Separatism

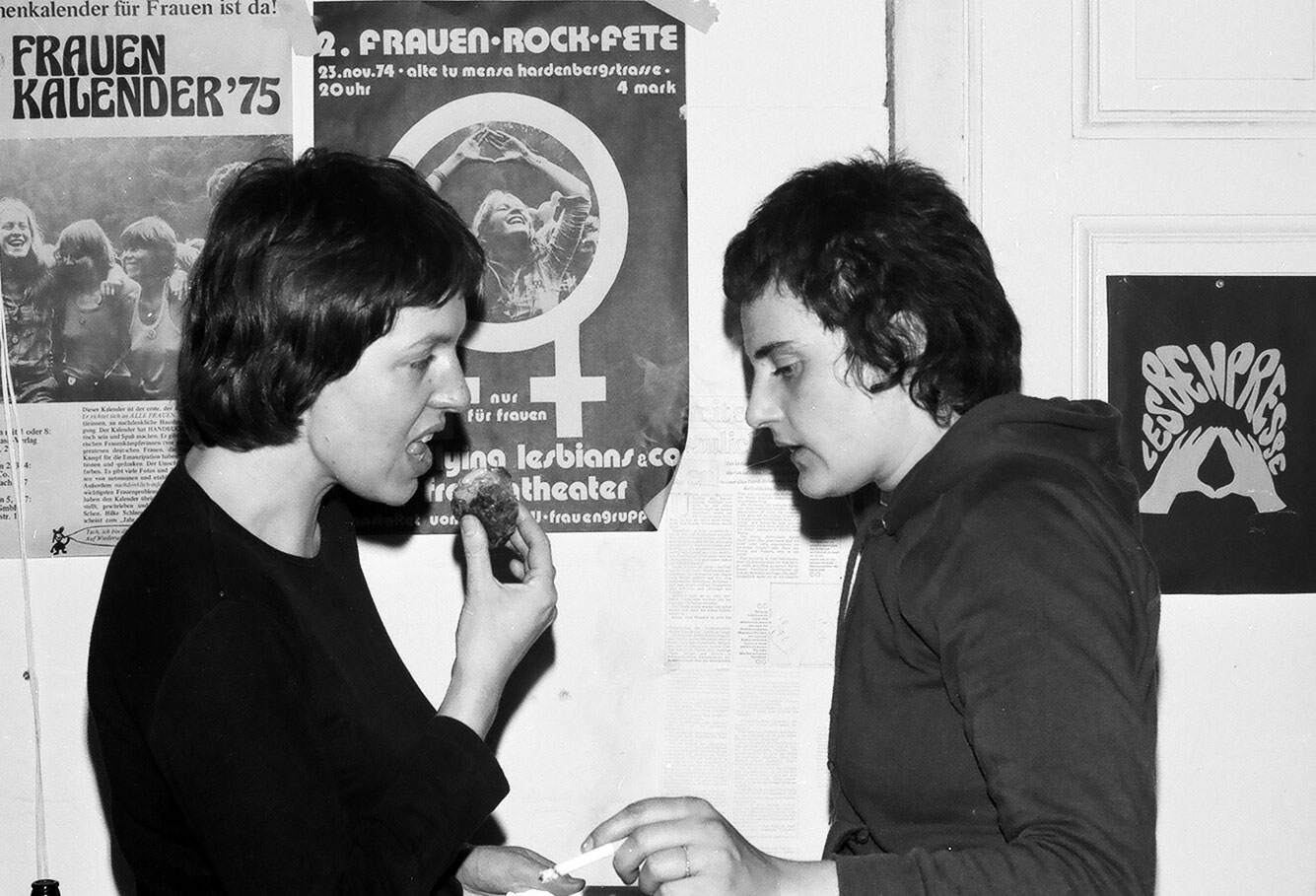

After moving into its own space[i] in April 1974, the women’s group of Homosexual Action West Berlin (HAW) gave itself a new name: the Lesbian Action Center (LAZ). In so doing they also signaled their separation from the HAW men’s group. A sub-group in the LAZ now cultivated this newfound identity by postulating lesbianism as the one true path: “Feminism is the theory—Lesbianism the practice” was their motto, inspired by Jill Johnston’s book.[ii]

Monne Kühn notes in retrospect:

I thought it was fabulous that a woman dared to develop such ideas, it can be quite liberating. But to translate it into reality… as in “gay is better”—this was fine as a provocation but I didn’t want women to force themselves to do anything… It was hotly debated; there were battles and battle lines. At that time I learned how differently people can deal with differences— and how to tolerate differences without going to war—a central theme in political work!

The older women and those with jobs left and founded the group L74; they held their meetings elsewhere but came to parties and the Pfingsttreffen. Here is Monne Kühn again:

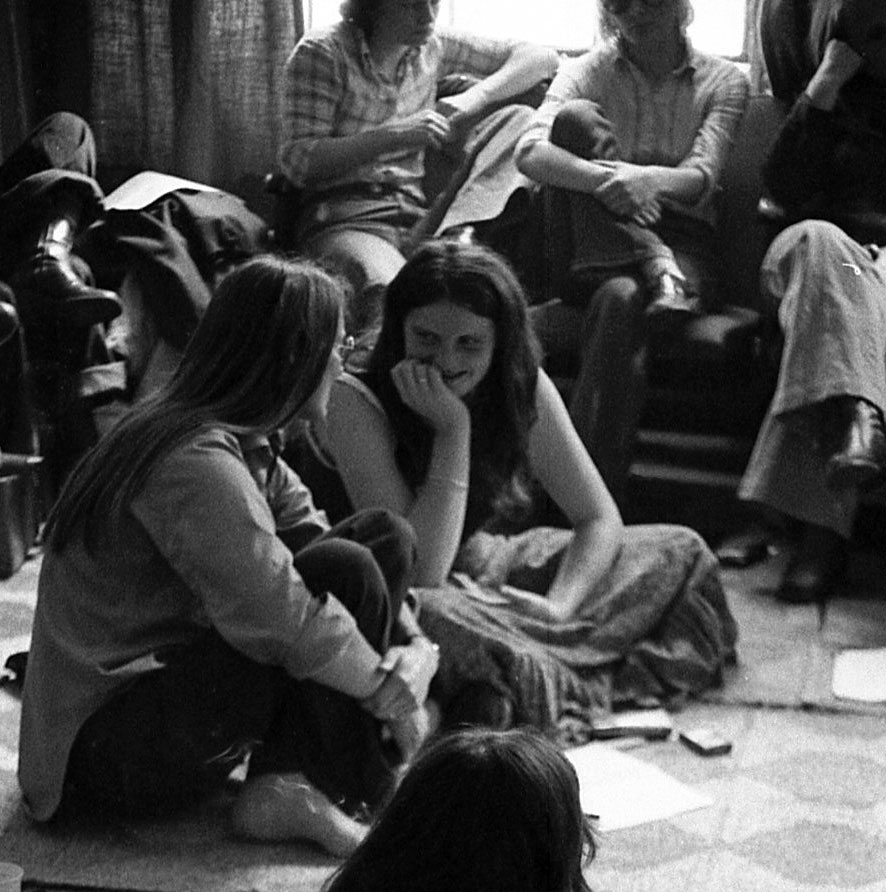

The LAZ had become rather student-centered [in the meantime], but lots of women from the bars came with quite different issues, many of them rejected our modes of behavior. They didn’t like that there were only mattresses to sit on. Many of them were employed and didn’t want to and couldn’t be as forthright as the giant fist on the wall breaking through the women’s symbol suggested. Some of the women were in their sixties and seventies.

The difference becomes clear from our publications: L74 published Unsere kleine Zeitung (Our Little Paper, UkZ)[iii] and the LAZ had Lesbenpresse…[iv] Lesbenpresse was distributed in West Germany, Austria, Denmark and Switzerland. This gave rise to the women’s book distribution service and we began translating and publishing books and articles from the USA.

Ilse Kokula, who was initially active in the HAW women’s group and then in L74, already wrote about the group’s formation in 1975:

The further development in LAZ brought with it an increasing rigidity and self-righteousness. One the one hand, it was necessary to attain new positions. But this was done very inflexibly, people no longer felt any need to be friendly to newcomers. We experienced our surroundings as extremely hostile in those days. We translated our fears into fiery speeches, getting high on our ideas, as it were: like whistling in the dark.

LAZ had about forty registered members, about ten of them active. We managed to accomplish quite a bit for such a small group: We organized the nationwide Pfingsttreffen every year, made two films, gave radio interviews, prepared the HAW documentation,[v] later the magazine Lesbenpresse, actions against the Springer press campaign and the trial in Itzehoe,[vi] keeping activities at the Center going with weekly meetings and lots of parties.[vii]

Pragmatism instead of social critique

I asked Ilse Kokula whether the pragmatism of today’s gay and lesbian movement doesn’t go too far: back in the day we wanted to smash the family and now gay men and lesbians are fighting for gay marriage. This was Ilse Kokula’s response:

We want the social and legal recognition of partnerships. As to marriage: We moved in student circles in those days, and everybody was against marriage. And nowadays even my best hetero girlfriends who resisted marriage for eighteen years are getting wed.

The social movement with global aims has given way to a series of “single-purpose movements,” associations with but one aim, to push through marriage rights for same-sex couples or promote sports for lesbians. We are operating on a lower floor, as it were, and looking at the pragmatic level.

Before, we had our eyes on the big objectives and forgot about improving everyday life. That is a shame, since I find a feminist-socialist perspective important. When I see the competitive pressures, for example in lesbian studies, there is an element once again of “I’m the best, I know better,” and the forward-looking aspect of social analysis is gone. In the early years, in contrast, we kept the whole context in mind.

The movement is much larger now, if more pragmatic and quieter. In those days we weren’t so interested in being in the limelight, while today, even if you are quieter about things, you are generally employed by a lesbian project, which is per se a fixed part of your professional career, parents get asked, “So, where does she work?”

We always wanted to be open, but didn’t succeed. According to the minutes, the lesbian group consisted of Hilde, Eva and Lisa. When you write to a government office now you have to sign your full name and are in the files forever. If I look at the lesbian police officers in Berlin-Brandenburg or Hamburg, they are open in everyday life, organized and out! Things were very different then.

The lesbian – a social construct?

Political aims aside, the way the lesbian movement views itself has also changed. Some people doubt whether lesbians even exist and whether the term is not simply an ascription.

Eva Rieger, who was active first in the HAW women’s group[viii] and then in L74, addresses this question:

An essay appeared in Ariadne[ix] [in 1996] where Andrea Bührmann criticizes and actually also ridicules lesbian studies more generally and my definition of a lesbian in particular. She says that in the age of postmodernism it is impossible to define THE lesbian anymore than THE man or THE woman, which is ultimately an overgeneralization and an ontologization.

Ever so modern, she refers to Judith Butler,[x] and says that we glorified the lesbian into a central model of resistance to the patriarchy. From today’s perspective that sounds terribly old-fashioned. These women refer to Claudia Honegger (Die Ordnung der Geschlechter)[xi] and Thomas Laqueur,[xii] who demonstrate historically that the gender binary is a product of the late eighteenth century, and that in earlier times a one-sex model dominated, that this binary perception of male-female is also social and only emerged at this time. This is all correct, but I nevertheless believe that we should not overlook the historical significance of certain steps.

We were of the opinion that there needed to be a lesbian identity. If society dismisses us as deviant and perverted and non-existent, we have to counteract this by becoming existent. That was an important step historically![xiii]

Today the fears are on a subtler level. Younger women students have told me this. They say, we can get the literature and talk about it, but our parents are as oppressive as ever, we still have to struggle to come out, and don’t believe for a minute that you were the only fighters.

Women’s projects

The first women’s projects in Berlin all emerged from the lesbian movement: First there was the women’s bar Blocksberg, then the rock band Flying Lesbians, two women’s bookshops and a women’s book distribution company, the women’s self-defense center—all of these exemplary women’s movement projects in Berlin were founded and run by lesbians. Lesbians were also the driving force behind the first projects that emerged from the Berlin women’s center: the women’s health center, the women’s therapy center PSIFF, the battered women’s shelter and the rape crisis hotline. The obvious pioneering role played by lesbians in the women’s center meant that heterosexual women felt under pressure. Women had to justify their relationships to men if not to their female friends then to themselves, which was sometimes difficult in light of men’s often extremely brutal behavior, with which we were confronted in those days in many of the areas in which we worked (hotline, women’s shelter, PSIFF, medicine, the legal system). The conflicts and synergies between the lesbian and women’s movements are the subject of the chapter Lesbian and Women’s Movements Synergize.

[i] A former factory building at Kulmerstrasse 20a, 3rd courtyard, 2nd floor.

[ii] Jill Johnston, Lesbian Nation: The Feminist Solution (New York, 1973), originally published in The Village Voice from 1969–72.

[iii] Unsere kleine Zeitung (UkZ), Berlin, 1975–2001.

[iv] Lesbenpresse, Berlin, 1975–1982.

[v] HAW-Frauengruppe (ed.), Eine ist Keine – gemeinsam sind wir stark, documentation (Berlin, 1974).

[vi] See the chapter Witch Hunt (1973) in part 2.

[vii] For an overview of the work of the HAW lesbian group, see Ina Kuckuc (Ilse Kokula), Der Kampf gegen Unterdrückung. Materialien aus der deutschen Lesbierinnenbewegung (Munich, 1975). The quotation is on p. 63.

[viii] See the chapter Little Band of Perverts.

[ix] Andrea Dorothea Bührmann, “Ist eine ‘Lesbe’ eine ‘Lesbe’? Anmerkungen zur Lesbenforschung angesichts der erkenntnistheoretischen Herausforderungen des Dekonstruktivismus,“ Ariadne – Almanach des Archivs der deutschen Frauenbewegung 11, no. 29 (May 1996): 60–67.

[x] Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York, 1990).

[xi] Claudia Honegger, Die Ordnung der Geschlechter: Die Wissenschaften vom Menschen und das Weib, 1750–1850 (Frankfurt a.M. and New York, 1991).

[xii] Thomas Laqueur, Making Sex: Body and Gender From the Greeks to Freud (Cambridge, MA, 1990).

[xiii] In a 2014 conversation Eva Rieger told me that it was the right thing in those days to insist on the term lesbian in order to make ourselves visible. In her view, it is equally important today to see the historicity of the word and to challenge it. See also Eva Rieger, “Vorschlag: Schafft die Lesbe ab!” EMMA 1 (2010): 144.