The courage to go public as a despised, “perverted” minority changes our self-image.

Although we recognized the importance of a women’s center, it would be two years before one opened in Berlin. Women were still fighting in mixed neighborhood committees for space for their issues, for women’s politics, while lesbians no longer felt the need to justify themselves to leftist men, and no accusations of “separatism” or “dividing the working class” could bring them back. It was also lesbians who were the first ones brave enough to organize as women on their own behalf, beginning in November 1971. One year later we called for the founding of a women’s center in Berlin. In the meantime, we had gathered useful experience in building an organization defined and run by women.

In order to understand the background to the women’s center and the women’s project movement one needs to study the lesbian group that preceded them. In the chapters that follow I will illuminate just a few aspects, namely the beginnings of the lesbian group within Homosexual Action West Berlin (HAW), the battles over theory, synergies with the women’s center and a comparison with lesbian culture today. I will dispense with a chronology of events, which Ina Kuckuc (the pseudonym of Ilse Kokula) already provided in her 1975 book Der Kampf gegen Unterdrückung (The Struggle Against Oppression).

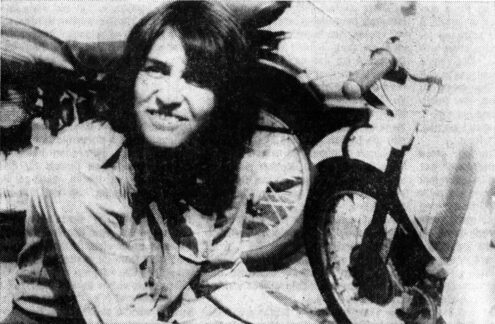

I met Waltraut Siepert in a women’s bar, and along with her a clique of lively lesbians from Kreuzberg and the Spandau allotment garden crowd. The latter women worked in the printing and photography business, while Waltraut was a legal secretary. They were “politicized,” but first and foremost they were individualists who had already taken their old cars on pilgrimages to Morocco or India, smoked hash and experimented with LSD. Among them I found the tenderness and sexual attention I had missed for so long in leftist circles. And so I left the women’s commune on Cosimaplatz in 1971 and moved to Kreuzberg. I worked in assembly for a few months at German Telephone Works (DeTeWe), then as a script girl at UFA studios, and I spent my Sunday afternoons with the women’s group in Märkisches Viertel.

Women riding (their own!) motorcycles without a helmet, hair blowing in the breeze must have been a pretty novel sight in those days. Inge Viett and Waltraut Siepert each had a motorcycle, a 250 cc BMW. I learned too when they sat me on a bike and pushed me until the motor caught. From then on I rode a motorcycle.

Rosa von Praunheim’s Film

In the summer of 1971 Rosa von Praunheim’s film It is Not the Homosexual Who is Perverse, but the Society in Which He Lives was shown in the Forum section of the Berlin Film Festival. I remember very well standing in the movie theater that day after the film was over, amidst a crowd of gay men embroiled in a vibrant discussion, men who were beginning to organize on their own behalf. Could women be involved too? Somewhat to my dismay, at the first meeting I heard rugged-looking men address each other with female names, which they clearly found rather thrilling. Without a doubt we would have been rather lost as individual women. But if we formed our own group the men promised to support us. Never before had I encountered this kind of unbiased, brotherly encouragement and affection from a group of men.

Gay Uprising in New York

A lesbian visiting from New York provided the final impetus for us to organize ourselves. She told us about the riot by queens at the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village, on June 28, 1969. “When the police [raid] could find no irregularities, they began abusing the customers and manager as ‘faggots’ and ‘fruits’.” This time the patrons refused to stand for it. “They tried to lock in the police and the manager and to barricade the surrounding buildings. An uprising lasting three days” began, which is now celebrated internationally as Gay Pride or (in Germany) as Christopher Street Day (CSD).

Homosexuals realized that they did not need such bars but could rent their own lofts and buy a few cases of beer. This practical, simple idea made immediate sense to Waltraut and me as well.

We had always suspected the owner of the Sappho[i] — a guy who drove around in a huge American convertible—of being a pimp, and the cell-like windows of the building over the bar of belonging not to an apartment house but to his brothel. The Sappho also let in voyeurs, men seeking lesbians for a threesome. I know a couple who were given a TV set in exchange for services contracted in the Sappho. We, the small lesbian community, thus saw ourselves as a sideline for pimps. These structures became apparent later, when Waltraut tried to push a voyeur she knew out of the Sappho: Within a minute, a gang of toughs had arrived at the bar, beating and kicking all of the defiant lesbians out the door. It was high time we freed ourselves of this humiliating situation on the margins of the sex trade.

[i] At the corner of Uhlandstrasse and Pariserstrasse.

Organizing Ourselves

But how could we reach other lesbians? Open agitation would get us booted out of the Sappho permanently, so we printed tiny flyers we could hide in our hands and pass on covertly in the bar. The flyers contained a single sentence as well as the time and place of our next meeting. Eight women ended up meeting in the S-Bahn Quelle, a hustler bar that we chose because it was less rough and they simply let us go about our business. Later we met at L’Inconnue at Goethestrasse 72–74 which, in the absence of the woman who owned it, was run by a collective of patrons to which Ulla Naumann also belonged. On February 6, 1972 gay men organized a screening of Rosa von Praunheim’s film at the Academy of Arts. From the stage there we made the first public appeal to found a women’s group within the Homosexual Action West Berlin (HAW). We had only been eight women up to that point, but more soon joined us. On March 3, 1972, together with the gay men from HAW, we moved into our new communication center, a dilapidated loft space in a rear courtyard at Dennewitzstrasse 33 in Schöneberg. Within this brief time, 100 women had already signed up for our address list.

From today’s perspective, this step towards self-organization seems obvious. Why didn’t it happen earlier, one might ask, why only now? There were already groups of school pupils or workers, and neighborhood centers organized by students who came from outside and were looking for something to get involved in where they could apply their knowledge and insights, but these groups fell apart as soon as the initiators withdrew. The HAW and the HAW women’s group had a new quality. Alongside the parent-run daycare centers, the HAW was one of the first autonomous, self-organized institutions in West Berlin. It also took courage to go public as a “perverted,” despised minority. And things requiring great courage also change the self-images of the people involved. That is why I would like to let three women who joined us in those days speak for themselves.

After taking her Abitur exams, E. R. worked for six years in the archives of the radio station RIAS and began to study at the music academy. She became a professor of musicology at the University of Bremen in 1991.

I come from a pastor’s family and felt very bound by those norms. I tried to live as a straight woman, had relationships with men eventually leading to an abortion, and could not face my erotic feelings towards women. When I was thirty I finally placed a personal ad and had my first relationship with a woman. When you tell younger women about this nowadays they laugh, it is incomprehensible to them. There was no literature, and the first films, The Children’s Hour with Audrey Hepburn, were just beginning to appear. The HAW women’s group was truly my salvation; first because I realized I wasn’t alone in the world, and second because I had the chance to find relationships and didn’t have to rely on personal ads. For me the lesbian bars felt like disreputable and immoral places, places I wasn’t supposed to go. I did go there, and I will never forget an older woman dancing with me and saying, “Go away, you don’t belong here,” which confirmed all of my prejudices. I don’t even like thinking about it, awful! At RIAS I had tried to approach a colleague. She said disdainfully, “I don’t like that sort of thing.” I felt terribly hurt.

That was what the HAW did for me, I didn’t have to go around thinking my sexuality was deviant; instead, my way of life could find complete acceptance. The psychological aspect was the most important thing about the HAW: You aren’t sick or perverted, you don’t belong on the trash heap of society, you can make loving women part of your life. That was an enormous change for me. I heard about the HAW from an old schoolmate; she handed me a flyer and said this was something for me. I asked her to come along. She left me at the door to the HAW because she felt inhibited. Then I went to Mutter Leydicke’s for some liquid courage and entered the HAW alone. I was afraid the women would be mannish, drinking one beer after another and chain-smoking… What I saw were women like me, in any case I felt at home from the beginning. Christel [Wachowski] took me under her wing right away and Gisela [Necker] also looked after me, I will never forget that. This lovely reception for new women was something I later repeated with others.

Ilse Kokula trained as a cook at the request of her father, who thought that a woman who could cook would keep her husband happy. Although she had no interest in the profession she finished first in her exams among all the trainee cooks in Bavaria. Then she went back to school and later trained and worked as a social worker. She went to the USA on a grant. At the age of 28 she moved to Berlin to study at the teacher training college (PH). She wrote her thesis on the evolution of the homosexual rights movement in Germany. Ten years later she was appointed professor at the University of Utrecht. In 1989 the Berlin government established an office for same-sex ways of life within the department of schools, youth and sports and Ilse Kokula was responsible for lesbian issues there.

Arriving at the HAW was my coming out. I had tried to meet homosexuals in Munich, but without success. I didn’t know whether I was homosexual—I had been in love, but unrequitedly—and I would have liked to have somebody to talk to about it, but it would be ten years before I was able to do that. I also tried to find books, but that was very difficult before 1970. I had been in Berlin for one year, then a student I was friendly with in one of my seminars told me about a friend of hers who was active with the lesbians in the HAW. I carried this around with me for about six weeks until I asked her whether she could introduce me to her friend. That was Doro Schemme. One very rainy November afternoon Doro walked around the block with me on Fuggerstrasse for hours. Then she had cleaning duty at the HAW. So I tagged along, helped clean and observed the women, watching how lesbians move. That was still on Dennewitzstrasse in the third rear courtyard. The lights in the stairwell didn’t work; it was always chilly and dark. You had to get there two or three hours early to heat the place, then it was a bit warmer. In the winter we sat around the heating stove. There were always problems with the sloppy men we shared the space with. So we were forever cleaning because we wanted to attract women from the bars, we wanted things to be nice and not so grungy. We sat on mattresses and there were a few rows of old seats along the walls from a defunct movie theater. In the first room was a curtain with more junk behind it. We sat on the floor and drank from bottles. When I arrived Waltraut Siepert took me out for schnapps. I found that so nice, I was still rather awkward at the beginning. But then I, too, greeted newcomers, they were quite nervous about the whole thing and often were brought to the stairs or the door by a gay male friend, a lot of them needed that help. We had to tempt women out of the bars, and if they were brave enough to come it was important to welcome them with a friendly word. For me it was liberating; I finally knew what I wanted.

Monne Kühn studied at the teacher training college (PH). She came from Freiburg and was not used to the big city and the bars, so she felt intimidated by Berlin. I had seen her several times standing outside the Sappho, not daring to go in. When she finally did go inside she saw that she had little in common with the other women. Before coming to the HAW she was active in the “Non-Dogmatic Left,” but felt alone and isolated as a lesbian. Being labeled a “pervert” was unbearable to her, and she had finally found women she could discuss this with, and who like her wanted to change this situation and social conditions. For that reason, finding the HAW women’s group was “a great good fortune and a joy.” Petra Lang was only involved in the early days. She was studying law, psychology and history at the time and later worked as a publishing representative.

I did not join the HAW not for the political actions. What was important to me was that women gathered there and I could talk with them. The women in the bars worked hard to conform as strictly as possible to the female norm in both clothing and body language, or they went to the opposite extreme, and I was not interested in this polarization. I found all this role nonsense really creepy. The HAW women’s group made some big changes for me because that is when I began to integrate being a lesbian into how I lived; this is me now, I share this with women who are not somewhere outside the rest of my life, but are just like me. Many friendships came out of this group. That is also where I met the girlfriend I later moved in with.

To be normal for a few days

A letter from Switzerland shows how far the influence of our self-organized lesbian group extended. After ten years of silence, I heard from the friend at whose wedding I had acted the part of a bridesmaid. She wrote

I would like to come to Berlin … to feel comfortable among people like me, not to be queer anymore, but to be normal among you, not to have to explain why I’m not normal, not to seek deep psychological explanations for why I am a lesbian, just to be with you all for a few days and see and hear that there are many women and girls who are the other way, to be normal for a few days and laugh at society and turn the tables for once, to feel strong and happy, to be a lesbian, to draw strength and courage from a big city, from a big group, I want to go to Berlin, faster than possible, write and tell me how to go about it…