Hunger Strikes at the Women’s Center and the Women’s Prison

The prison group was one of the first working groups at the Berlin women’s center. The group’s existence belies the image of the new women’s movement painted by authors who reduce it to abortion counseling and consciousness-raising groups and are unfamiliar with its anarchist roots.

The prison group took on individual women inmates, including “apolitical” ones such as Paula Weiß, Gisela Weiß and others. Two of the women in the group had themselves just been released from prison, but the driving force was Waltraut Siepert, who shortly thereafter was convicted of supporting a criminal organization (she had rented an apartment for members of the June 2nd movement) and would spend three years in the isolation wing of the men’s prison in Moabit and one year in the women’s prison at Lehrter Strasse 60/61. At the time when the Berlin women’s center was founded, her girlfriend of many years Inge Viett was incarcerated at this women’s prison, until she broke out in August 1973. Two other women from the early years of the women’s center, Gabriele Rollnik and Gudrun Stürmer, joined the June 2nd movement. Together with other women Rollnik sprung Till Meyer from Moabit prison, and when she was incarcerated at Lehrter Strasse prison, she and three other women managed to abseil out in July 1976.

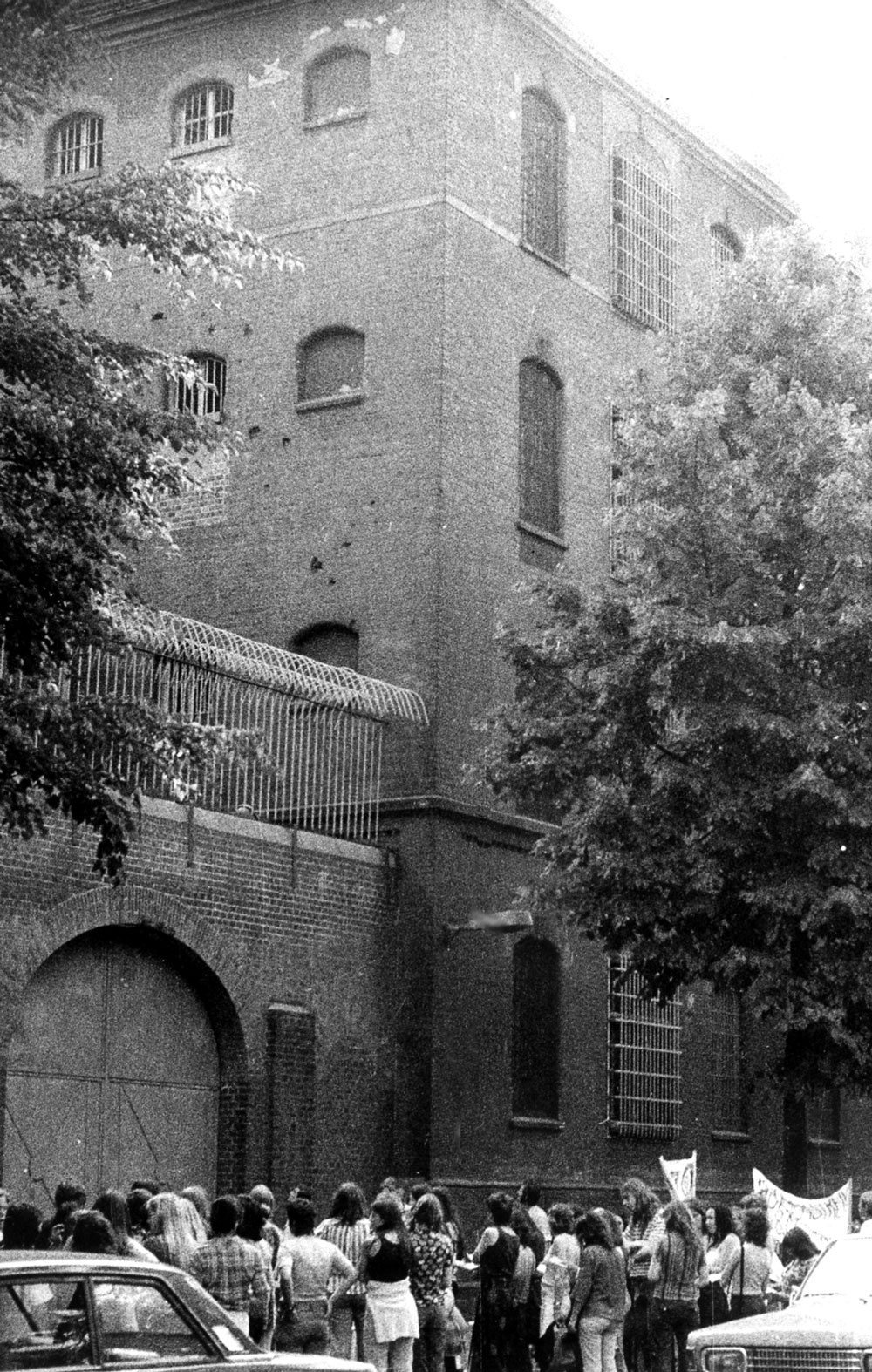

Photo: Cristina Perincioli

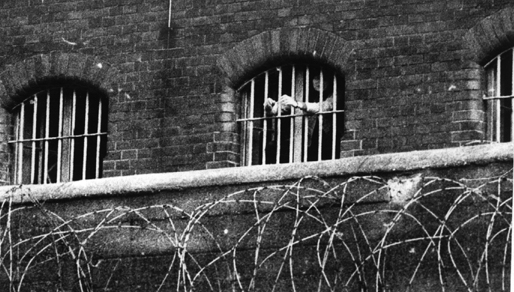

At the back of the Lehrter Strasse prison is a public footpath leading to the Poststadion. Waltraut Siepert had discovered that one could stand there and converse with inmates over the wall if their cells were on that side. Why all this effort? It was common for political prisoners to wait many years before trial. In this period of pretrial detention, their mail was often censored and they were frequently allowed no visitors, or at most every two weeks, and in some cases only family members. Inge Viett had grown up in foster care and therefore had no visitors. So Waltraut often went to the prison wall in the evening to find out how her friends and acquaintances were doing. At the time Waltraut thus both supported the June 2nd movement and was active in the women’s movement as the founder of the women’s group of Homosexual Action West Berlin (HAW) and the Berlin women’s center.

In a letter of May 18, 1973, Cillie Rentmeister wrote:

A hunger strike has broken out again at Lehrter Strasse [women’s prison], and fifty to sixty women and men make a torchlight procession to the slammer.

It went very well. Imagine, about nine in the evening, just getting dark, us singing women’s and jail songs, speaking or rather shouting to the women inside who perch on their lockers so they can see us through the bars.

Then they sing us a song, a “love song” because we are all so great. A little while later little fires flare up in the cells: matches. Soon they hold burning paper torches through the bars, and then burning articles of clothing fly out of the prison and they hold burning brooms through the “windows”— you obviously develop a lot of imagination in prison.

But more and more police arrive, they issue an ultimatum, try to arrest Helga [Pahl], the women finally retreat, but only after their cars are searched.

Flyer

In October 1973 the prison group women distributed a flyer entitled “Solidarity with Our Sisters in Lehrter Strasse Women’s Prison”:

Our sisters in jail have been on an open-ended hunger strike for almost two weeks now [on October 13, 1973]. The impetus was various measures taken by the new prison warden Maas and his staff of guards. For example, the installation of additional steel mesh—so-called fly screens[i]— on ALL cell windows, which totally obstructs contact among inmates, so they can’t even stretch a hand or hang their legs through the bars, allowing at least one part of their bodies to enjoy the sun and air. Our sisters “resisted” by sitting at the windows and refusing to get down in order to hinder the workmen from installing the fly screens.

Everybody needs to know what is going on! In response to this passive resistance, they brought the special police unit from Moabit prison, whose members violently dragged four sisters into the bunker and as usual made brutal use of their rubber truncheons and manly strength. There should be no room in our state for torture, abuse and the death penalty.

THEY EXIST!

Everybody needs to know what is happening there!

The fly screens are only the least of the chicanery and isolation prisoners are forced to suffer every day. Those of us living in the big open-air prison refuse to accept the torture of our sisters anymore and we are going on hunger strike for one week.

WE ARE HUNGER STRIKING TOGETHER AT THE WOMEN’S CENTER[ii]

Hunger strike at the women’s center

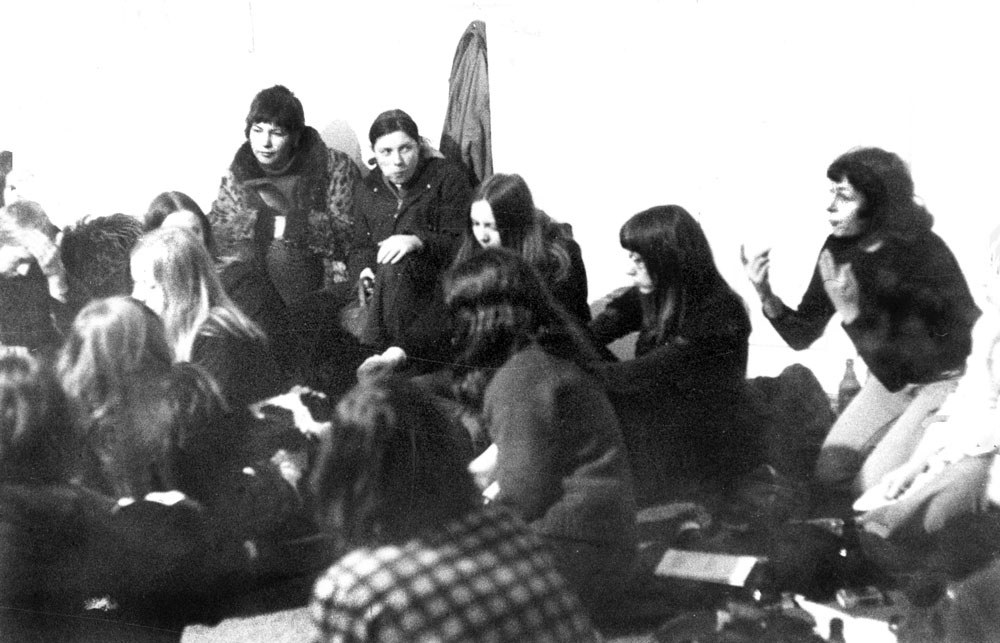

The hunger strike was a new experience for all the Center women who participated, but we took a cautious approach, as I told my mother in a letter in October 1973:

Your description of the wedding menu came at a rather inopportune moment since we are currently on a week-long hunger strike. Reading about your “ham baked in pastry” drove me crazy…

We—20 women from the FZ [women’s center]—are on this hunger strike to gain attention for the hunger strike in the women’s prison. There, 17 women are refusing food, in the fourth strike this year already, and the press has not reported on it at all so far in spite its being the last resort for inmates who want to draw attention to their terrible conditions. Many have already been force-fed, some of them even strapped down. Our hunger strike has at least succeeded in getting some press and radio time. The hunger strike is quite a fascinating experience, by the way: I would never have thought myself capable of it since I enjoy eating so much and become quite grumpy if I have to wait for food and can barely keep upright without breakfast. You can get pretty dizzy, but what does it matter? And what’s the big deal if you fall back onto a chair when you try to stand up?

The important thing is, we’re not lying around, and we feel very strong and clearheaded. I haven’t worked this hard in months: on my feet 16 hours a day and the time usually spent eating is available for other activities (no washing dishes, cooking or shopping either!)

A strange, inexplicable feeling, to sleep splendidly with nothing in your belly; to wake up in the morning with an empty stomach and not be hungry at all, to feel light and strong, start working right away and often feel better during the day than one does with food.

In the meantime I find even salty tea delicious. You need to get salt somehow, either by licking it off your moistened finger like a pretzel stick, or in a drink. Sugar is the greatest torture at the moment, we avoid it, even half a spoonful in tea causes immediate hunger pangs, and they can plague you for hours! In prison they put fructose in the inmates’ water, for example; the doctors use it to try to break the hunger strike because the effects of sugar are so devastating.

I have tried it above all in order to get some distance from this consumption-mad world, this greed that dominates us—more than we think— the awareness of having to possess this or that in order to be able to work… It makes me happy to see how much strength a body has, and that one can meet the challenge without fear. Some women have quit, however, complaining that they felt unwell, and they believe they can work better if they eat… In any case, they have reason to envy us our experience.

Hunger strike in prison

What did it mean for the women in prison to go on hunger strike, though? They planned everything during yard exercise or by secret messages passed from one inmate to another. Women who had jobs lost them, which is why they usually didn’t participate. Instead of accepting food, the strikers put out a declaration that they were on hunger strike and had demands.

Among political prisoners, 80 percent of hunger strikes were successful to some degree. However, these hunger strikes often lasted several weeks, and even months. Without this weapon, the conditions of imprisonment would have been far harsher, though. The prison administration did everything they could to break the hunger strikes. Some doctors had themselves signed off work to avoid participating. As a last resort, prisoners refused fluids, and then they were hospitalized. It was only then—when they were near death— that any concessions were offered. This was a means of struggle that the opposing side respected. Even the turnkeys admired the prisoners for their courage.

Reactions from the media, the street and other groups

According to the plenary minutes from October 1973,

Press conference Thursday: A woman from SFBeat [a radio show on Sender Freies Berlin] (Magdalena Kemper) came and right away played the tape on which she interviewed Rossbacher and Maas, the head honchos from Lehrter women’s prison, allowing an immediate response to their lies—the fly screens were allegedly only installed on a few windows with contact to the outside, although in reality these screens mainly prevented the inmates from communicating with one another. Unfortunately, the most extreme passages were later deleted from the tape for broadcast. The reporter had been offered the alternative: “either there will be no program at all or we censor it,”[iii] and since she wanted the public to hear at least something about the disgraceful conditions and the resistance against them, only the remainder of the interview was broadcast. The women in prison could hear the show too, which pleased them no end and of course boosted their struggle.[iv]

The Spandauer Volksblatt newspaper of October 26, 1973 wrote on the title-page:

Yesterday, 20 women from a Kreuzberg initiative embarked on a hunger strike to protest “inhumane prison conditions” and “modern torture methods.” They planned the action out of solidarity with eleven inmates at Lehrter Strasse women‘s prison.

The story continues on page 12 of the newspaper:

The women explained their demands in a discussion with the press: “The abolition of the bunker as a medieval instrument of torture… The prison used to have no bunker at all, then one and now four, which were occupied in no time at all.” Warden Maas deployed goon squads more and more to discipline the women prisoners. Their third demand concerning the clearing out of the cells was especially serious, since afterwards the inmates had to spend days vegetating with no working or reading materials, cigarettes or personal effects…. According to the women, the police “made liberal use of rubber truncheons and chain nipper handcuffs (Knebelketten)” during their operations. One spokesman for the justice system said that it was perfectly normal for police officers to carry rubber truncheons and chain nippers during such an operation. He denied the accusation that wet towels had been held against the inmates’ mouths to muffle their screams.

The newspaper account cited our demands in detail. The author was Monika Mengel. I visited her in the newsroom and invited her to participate in our media group.

Apart from publicity, the prison group engaged in direct action on the street. The minutes report:

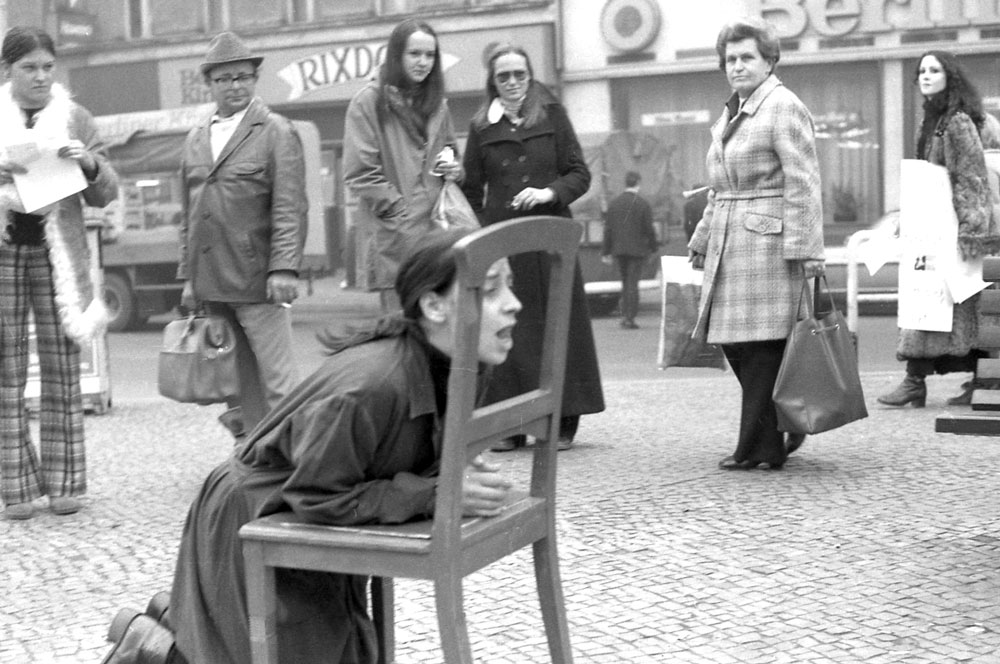

Photo: Cristina Perincioli

Every afternoon several women set off with their faces painted white and wearing sandwich boards containing information on the prison hunger strike. Different women interpreted the responses to this action differently: Some felt only aggression from the population and found perhaps one person among 100 who understood what was going on because s/he had been in prison, while another woman regarded it as a positive experience; Hermannplatz was in a working-class neighborhood and the people were far more interested than in the abortion discussion, for example.

Many came from outside to support the action, e.g. women and men from HAW, Rote Hilfe, the [Tommy] Weisbecker Haus.

Social work students joined another demonstration outside the women’s prison:

We were about 60 people then, with a megaphone and a red flag, and we all met in the Tiergarten [park], [walked to the women’s prison] singing a song, and by the time the pigs arrived with their police vans it was all over. The women in prison had heard us.[vi]

Social work in the women’s prison

How did the prison staff experience the hunger strike? I spoke about this with Ms. Brandt, a social worker in the Berlin women’s prison for many years. The women’s prison has since moved to a new building, but at the time it occupied a hundred-year-old former military prison on Lehrter Strasse. The prison saw countless hunger strikes during the years when terrorists were incarcerated there.[vii] Most of them lasted six to eight weeks or longer; others, like the one we supported, targeted prison conditions more generally, and apolitical prisoners also participated, for which reason the strikes were usually shorter. In our conversation I asked Ms. Brandt whether she had found such a hunger strike stressful:

Of course I found it stressful. Because I couldn’t work anymore: How are you supposed to work in a building where people are trying to starve themselves to death? Some of them were not even capable of dialing down a notch anymore. If I think of Ms. [Brigitte] Mohnhaupt, I am quite certain that at times she was physically no longer in a position to say stop, sometimes she had already crossed the line.

– How did this mess up the whole place? It was always just a few people?

– How can I explain this? If somebody up front at the main office is shouting the whole place is in an uproar, nobody knows what’s going on, they just hear something and that makes you feel like something is happening, something is happening at long last, nobody knows what or the reason why, and that is exciting.

– But a hunger strike is silent.

– But people talk about nothing else, everybody is upset, especially at those who aren’t doing anything. The atmosphere towards us was never as horrible as at that time. We were the jailers. And when we opened a cell door all hell broke loose. People threw stuff at us. Because if I have a core of rebellion and [as a normal inmate] I also feel that I want to do something but can’t, then I cling to this core. Then you couldn’t work with anyone anymore.

In her opinion, the installation of the fly screens only affected the cells on the street side, from which dealers could easily supply the drug-addicted women and youths. They wanted to put a stop to this. Ms. Brandt could not remember punishments in the bunker or the brutal police deployments:

The police were only deployed once, and the women smeared the floor tiles in the corridors with soft soap. The police sailed down the halls and fell on their butts and were pretty badly hurt, since the women had broken all the lamps with broom handles, every single neon tube. The hunger strike aside, what are you supposed to do with people in a place like that? You can’t offer them any meaningful work or leisure activity—what have you got to offer them? I can offer you a conversation, but what’s the point? You feel like an idiot.

The youths—just imagine— they had nothing, no school, nothing—where would they have gone?

In the women’s prison, the untenability of conditions practically overlapped with political events and that made everything so acute. These conditions were in the public eye for the first time, this had never happened before, never! If there are no riots, if the bed sheets aren’t hanging out the windows and people aren’t escaping and sawing through the bars, well, then there is nothing going on. To have a penal system under these horrible and miserable conditions—better not to have one at all.

–So why didn’t you join in with your own demands?

–Yeah right, just go ahead and try that, it isn’t so easy as a civil servant, you have to do everything via your superiors and that is it. You would have had to leave. And many did leave.

[i] The lawyer Henning Spangenberg describes the effect of the “fly screens” in the documentary film “Der Terroranwalt.” He spoke with his client in his cell: “There was a screen on the window, a very dense gray steel mesh. It was a splendid autumn day, blue sky, sun, gorgeous. I sat with him in the cell and talked for about an hour. I’m on my way out of the prison and think to myself: Oh crap, it’s raining, gray sky, miserable, such lousy weather! I walk outside and see: blue sky and sun. It suddenly became clear to me that my senses were disoriented by this one short hour…” Frauen and Film 18 (1978), 7–12.

[ii] Berlin women’s center flyer, October 1973.

[iv] Minutes of the October 30, 1973 plenary at the Berlin women’s center.

[vi] Minutes of the October 30, 1973 plenary at the Berlin women’s center.

[vii] See the report on an incident of April 28, 1973 at the Lehrter Strasse women’s prison in Kursbuch 32 (August 1973), pp. 157–58. The inmates mentioned are clearly Inge Viett, Verena Becker, Katharina Hammerschmidt and probably Annerose Reiche.