Selbstverteidigung/ Konzept eines autonomen Frauenhauses/ Tribunale

Selbstverteidigung gegen männliche Gewalt

Zuerst hatten wir nur die diffuse Absicht, jeder Frau in Schwierigkeiten zur Seite zu stehen und uns nicht mehr zurückzuziehen und wegzuschauen, wie wir es in der Vergangenheit getan hatten. In diesem Sinne hielten wir anarchistischen Frauen, als eine Barbesitzerin um unseren Schutz bat, an ihr fest und wurden von ihrem Ehemann und männlichen Gästen für unsere Mühe geschlagen. [ich]

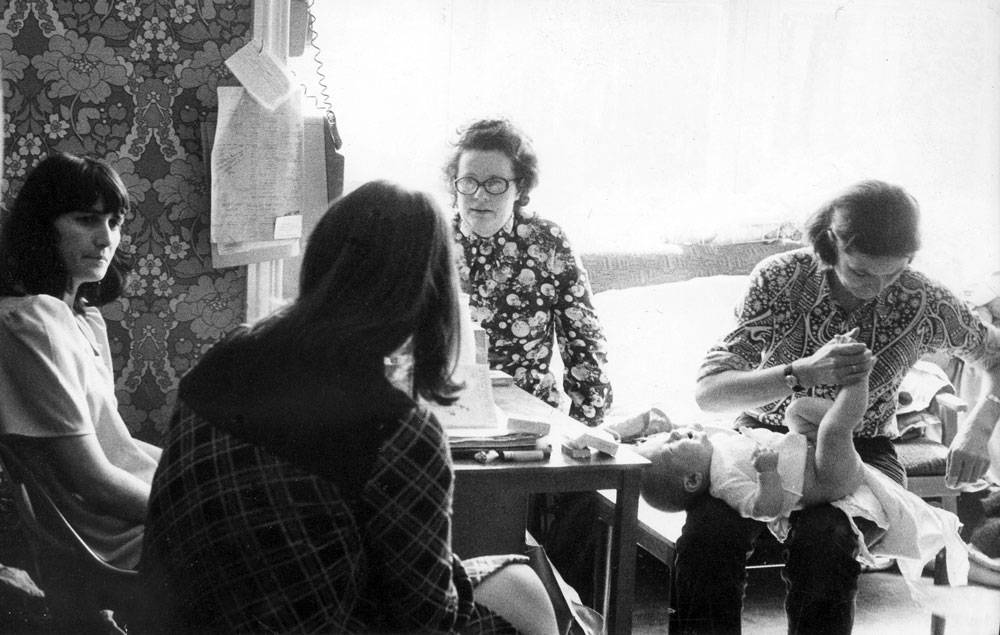

In 1973 women from the women’s center and the HAW studied Tae Kwan Do with a man. When the karate instructor Martha Schediwy appeared on the scene—one of the first in her field and a black belt— a few women got together to found Self-Defense for Women at Hauptstrasse 9 in Berlin’s Schöneberg district. Here we learned karate and self-defense techniques specially designed for women. Martha emphasized, however, that technique alone was not enough: We also had to toughen up. We learned how to take blows without complaining and practiced pushups on our fists—on a surface of sharp gravel to build calluses. The training also included running, weightlifting, learning to fall, karate kata, self-defense moves and role-playing in which we practiced getting out of dangerous situations unscathed. After all, women often hold back in conflicts with men until it is too late, while decisive resistance confuses the attacker, making escape possible.

Photo: Cristina Perincioli

The first women’s shelter

The first women’s shelter on the European continent was opened in Berlin in 1976 and the first rape crisis hotline in 1977. Up to that point, women in trouble had often contacted the women’s center directly. We didn’t just comfort them, but tried to offer immediate, concrete help. For example, we enabled one woman to go back to the apartment she had fled because of her violent husband and pick up her clothes. Trembling with fear, we stood outside the apartment door behind which a thug with dogs awaited us. But then the door sprang open and we stormed in. The man had no idea how to react, completely surprised to find that his wife suddenly had so many friends.

Another time we tried to protect a woman in her home. Her husband and grown son abused her regularly. For an entire week we took turns standing guard at her villa in the Grunewald district. Her son nevertheless managed to push his mother down the stairs in an unwatched moment.

In 1973 women in Copenhagen had occupied an entire building and set up a bookshop and counseling center. In 1974 we heard of another women’s squat, this time in London. I hitchhiked there with Monika Mengel and found whole streets of squatted buildings in Brixton. The squatter movement made use of an old law that permitted people to take possession of abandoned houses. Brixton had gradually been taken over by immigrants from the Commonwealth, and better-off people left the neighborhood. I, too, soon lived in one of the spacious townhouses with a garden.

Photo: Cristina Perincioli

A few women who had found refuge in the now-overcrowded first London women’s shelter that Erin Pizzey set up in Chiswick went on to squat a second house in Brixton and were in the process of renovating it. What I admired as a bold action they found perfectly ordinary. The only thing that worried them was the impending plumbing work.

1974 no term yet for domestic violen

In 1974 there was no term yet in German for domestic violence (in those days we spoke of “battered women”), and except for those directly concerned—who remained silent—nobody had any idea of what that meant concretely. The Englishwomen told me their stories on tape, stories from a parallel world of incomprehensible cruelty! Back in Berlin I sought out more cases of domestic violence and asked the women’s center plenary if anyone knew women who were being beaten by their husbands. I was quite astonished when women from the women’s center groups spoke up to say they were personally affected, women I thought I knew, women I had worked with! It wasn’t “the others” who had this problem, it was right there among us! The perpetrators in this case included a theater lighting technician, a cameraman and a manager at IBM, and their stories were no less nasty and brutal. My interviews and contacts became the material for my own radio segments, Sarah Haffner’s documentary film Schreien nützt nichts. Brutalität in der Ehe (No Use in Screaming: Brutality in Marriage)[ii] and the book Gewalt in der Ehe und was Frauen dagegen tun (Violence in Marriage and What Women are Doing About It),[iii] which I wrote together with Sarah Haffner. They also provided the basis for my docudrama The Power of Men is the Patience of Women.[iv] Through various media, we thus paved the way for an awareness of the necessity of women’s shelters. The first one in Germany was founded in Berlin in 1976 by women from the women’s center.

Photo: Cristina Perincioli

22 Hz

44Hz

[i] See the chapter Women’s Commune.

[ii] Sarah Haffner, Schreien nützt nichts. Brutalität in der Ehe, WDR, 1976.

[iii] Sarah Haffner (Hrsg.), Gewalt in der Ehe und was Frauen dagegen tun (Berlin, 1976).

[iv] Cristina Perincioli, Die Macht der Männer ist die Geduld der Frauen , ZDF, 1978.